The boundary between electronics and biosystems is an increasingly important research area1. On one hand, biosystems provide enormous inspiration for advancing electronics through functional emulations2,3,4; on the other hand, bio-emulated electronics are often used to interface with biosystems to gain further biological understanding or improve biological functions5,6,7. These two directions often benefit each other mutually. A notable example is the development of memristors and associated neuromorphic electronics. The analog conductance modulation in nonvolatile memristors was initially used to emulate synaptic plasticity8, which was later incorporated into neural computing networks9,10,11. Similarly, the spontaneous conductance relaxation in some volatile memristors has been employed for constructing basic integrate-and-fire neuronal functions12,13, with potential applications for spiking neural networks. Concurrently, the bio-emulated functions of these neuromorphic devices make them promising candidates for improving signal translation in bioelectronic interfaces14,15,16,17,18,19.

Developing artificial neurons with improved functionalities is of particular interest because neurons inherently possess rich computing capabilities12,13. Expanding the functionality of artificial neurons to more closely match their biological counterparts can lead to more efficient signal processing with reduced circuitry and energy consumption13,14, which is especially beneficial for bioelectronic interfaces. To achieve this, artificial neurons have been constructed using various devices to emulate basic neuronal functions, such as spiking generation and signal integration12,13,14,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The integration functions are further utilized to process bioelectronic signals from environmental, bodily, and physiological stimuli for bio-realistic interpretation14,15,16,17,18,31,32,33,34,35.

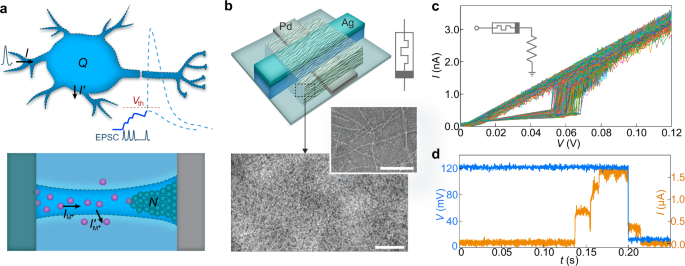

Despite advancements in functional emulation, a significant gap remains between artificial neurons and their biological counterparts. Specifically, biological neurons use ultralow signal amplitudes (e.g., action potentials of 70–130 mV)36, whereas demonstrated artificial neurons work with amplitudes ≥0.5 V12,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The ultralow amplitudes facilitate seamless signal flow between sensory and computing functions in biosystems, enabling exceptional processing efficiency. Therefore, achieving parameter matching is crucial for enhancing efficiency in bio-emulated/integrated systems, including improving signal translation in bioelectronic interfaces. Recently, memristors with ultralow operating voltages were used to create artificial neuronal components, demonstrating that bio-amplitude signals (e.g., <130 mV) could induce state changes16,25,32,37. The state change was further manifested by threshold event of a current spike mimicking neuronal firing32. However, the discontinued (one-time) current spike still differs from repeated voltage spikes seen in actual neuronal firing, limiting the potential for signal cascading and realistic bioelectronic interactions.

We demonstrate artificial neurons capable of integrating bio-amplitude signals and producing continuous voltage spikes that resemble action potentials. The artificial neurons are built from a type of memristor uniquely designed to operate with ultralow voltage and current signals. The construct incorporates components that can fundamentally emulate key dynamic processes involved in neuronal firing. As a result, these artificial neurons achieve not only close functional emulation but also parameter matching in crucial aspects such as signal amplitude, spiking energy, temporal features, frequency response, and dynamics tuning. Moreover, these artificial neurons can be integrated with chemical sensors to emulate neuromodulation by extracellular substances (e.g., ions and neurotransmitters) in a manner consistent with biological neurons. Furthermore, we demonstrate that an artificial neuron can connect to a biological cell to process cellular signals in real time and interpret cell states. These advancements enhance the potential for constructing bio-emulated electronics to improve bioelectronic interface and neuromorphic integration.