Scientists are trying to bottle solar enScientists are trying to bottle solar energy and turn it into liquid fuel

Get the Mach newsletter.

By Wayt Gibbs

What if we could bottle solar energy so it could be used to power our homes and factories even when the sun doesn't shine?

Scientists have spent decades looking for a way do just that, and now researchers in Sweden are reporting significant progress. They've developed a specialized fluid that absorbs a bit of sunlight's energy, holds it for months or even years and then releases it when needed. If this so-called solar thermal fuel can be perfected, it might drive another nail in the coffin of fossil fuels — and help solve our global-warming crisis.

Unlike oil, coal and natural gas, solar thermal fuels are reusable and environmentally friendly. They release energy without spewing carbon dioxideand other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

"A solar thermal fuel is like a rechargeable battery, but instead of electricity, you put sunlight in and get heat out, triggered on demand," says Jeffrey Grossman, who leads a lab at MIT that works on such materials.

A MOLECULAR JEKYLL AND HYDE

On the roof of the physics building at Chalmers University of Technology in the Swedish city of Gothenburg, Kasper Moth-Poulsen has built a prototype system to test the new solar thermal fuels his research group has created.

As a pump cycles the fluid through transparent tubes, ultraviolet light from the sun excites its molecules into an energized state, a bit like Dr. Jekyll transforming into Mr. Hyde. The light rearranges bonds among the carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen atoms in the fuel, converting a compound known as norbornadiene into another called quadricyclane — the energetic Mr. Hyde version. Because the energy is trapped in strong chemical bonds, the quadricyclane retains the captured solar power even when it cools down.

To extract that stored energy, Moth-Poulsen passes the activated fuel over a cobalt-based catalyst. The Hyde-like quadricyclane molecules then shapeshift back into their Jekyll form, norbornadiene. The transformation releases copious amounts of heat — enough to raise the fuel's temperature by 63 degrees Celsius (113 degrees Fahrenheit).

If the fuel starts at room temperature (about 21 degrees C, or 70 degrees F), it quickly warms to around 84 degrees C (183 degrees F) — easily hot enough to heat a house or office.

"You could use that thermal energy for your water heater, your dishwasher or your clothes dryer," Grossman says. "There could be lots of industrial applications as well." Low-temperature heat used for cooking, sterilization, bleaching, distillation and other commercial operations accounts for 7 percent of all energy consumption in the European Union, Moth-Poulsen says.

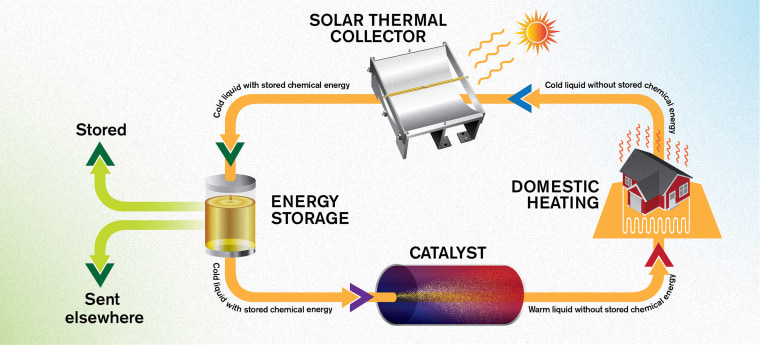

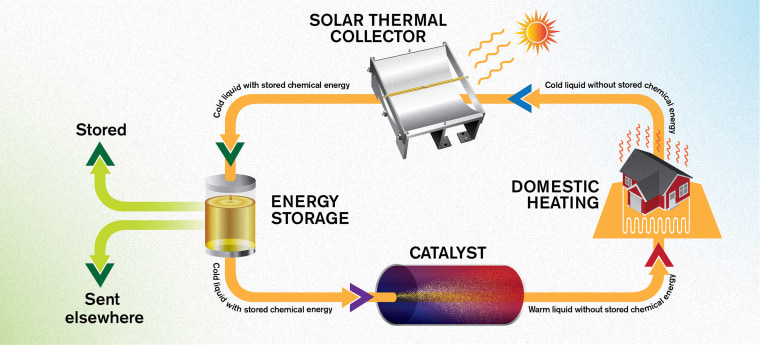

A solar thermal fuel could be stored in uninsulated tanks inside houses or factories — or perhaps piped or trucked between solar farms and cities. Very little of the fuel or the catalyst is damaged by the reactions, so the system can operate in a closed loop, picking up solar energy and dropping off heat again and again. "We've run it though 125 cycles without any significant degradation," Moth-Poulsen says.

HEAT WITHOUT FIRE

Moth-Poulsen has calculated that the best variant of his fuel can store up to 250 watt-hours of energy per kilogram. Pound for pound, that's roughly twice the energy capacity of the Tesla Powerwall batteries that some homeowners and utilities now use to store electricity generated by solar panels.

"I'm very excited by what Kasper is doing," Grossman says of the research. After a burst of work on norbornadiene fuels in the 1970s, he says, chemists were stymied. The fuels kept breaking down after a few cycles. They didn't hold their energy very long, and they had to be mixed with toxic solvents that diluted the energy-grabbing fuel. Moth-Poulsen "has gone back to that molecule and is using state-of-the-art tools to fix it," Grossman says.

The new results, published in a series of scientific papers over the past year, have caught the attention of investors. Moth-Poulsen says numerous companies have contacted him to discuss the potential for commercialization.

FROM PROTOTYPE TO PRODUCT

For all the promise of solar thermal fuels, years of development lie ahead. "We've made a lot of progress," Moth-Poulsen says, "but there is still a lot to figure out."

A crucial next step will be to develop a single fuel that combines the best characteristics of the many fuel variants the Chalmers team has developed — including long shelf life, high energy density and good recyclability.

Wei Feng, who leads a research group working on solar thermal fuels at China's Tianjin University, points to solvent-free operation as another "big challenge for future commercialization."

Moth-Poulsen's prototype fuels are made via common industrial processes and from widely available industrial agents, including derivatives of acetylene. But it's unclear how much a commercial version of the fuel would cost.

One important factor in the cost will be the fuel's efficiency, which currently is quite low. The prototype fuels respond only to the shortest wavelengths of sunlight, including ultraviolet and blue, which account for just 5 percent of the solar energy available. Moth-Poulsen says he's working to extend the fuel's sensitivity to include more of the spectrum.

He's also aiming to break his own record of a 63-degree C temperature increase. When that heat is added to water that has been preheated to 40 degrees C or more by conventional solar collectors, he says, "That's just enough to boil water into steam." The steam could then drive turbines to make electricity. But with more tweaks to the chemical structure, he says, "I think we could push [the temperature increase] to 80 degrees C or higher." For electricity generation, hotter is better.

"When I started, there was really only one research group working on these kinds of systems," the 40-year-old Moth-Poulsen recalls. But progress has drawn others to the challenge. "Now there are teams in the U.S., in China, in Germany — about 15 around the world," he says.

¿Qué pasaría si pudiéramos embotellar energía solar para poder utilizarla en nuestros hogares y fábricas incluso cuando el sol no brilla?

Los científicos han pasado décadas buscando una manera de hacerlo, y ahora los investigadores en Suecia están reportando un progreso significativo. Han desarrollado un fluido especializado que absorbe un poco de la energía de la luz solar , la retiene durante meses o incluso años y luego la libera cuando es necesario. Si este llamado combustible termosolar se puede perfeccionar, podría clavar otro clavo en el ataúd de los combustibles fósiles , y ayudar a resolver nuestra crisis de calentamiento global.

A diferencia del petróleo, el carbón y el gas natural, los combustibles térmicos solares son reutilizables y respetuosos con el medio ambiente. Ellos liberan energía sin escupiendo dióxido de carbono y otros gases de efecto invernadero a la atmósfera.

"Un combustible térmico solar es como una batería recargable, pero en lugar de electricidad, se pone la luz del sol y se elimina el calor, que se activa según la demanda", dice Jeffrey Grossman, quien dirige un laboratorio en el MIT que trabaja con dichos materiales.

UN JEKYLL MOLECULAR Y HYDE

En el techo del edificio de física en la Universidad de Tecnología de Chalmers en la ciudad sueca de Gotemburgo, Kasper Moth-Poulsen ha construido un prototipo de sistema para probar los nuevos combustibles térmicos solares que ha creado su grupo de investigación.

Cuando una bomba hace circular el fluido a través de tubos transparentes, la luz ultravioleta del sol excita sus moléculas a un estado energizado, un poco como el Dr. Jekyll transformándose en el Sr. Hyde. La luz reorganiza los enlaces entre los átomos de carbono, hidrógeno y nitrógeno en el combustible, convirtiendo un compuesto conocido como norbornadieno en otro cuadriciclano llamado - la versión energética de Mr. Hyde. Debido a que la energía está atrapada en fuertes enlaces químicos, el cuadriciclano retiene la energía solar capturada incluso cuando se enfría.

Para extraer esa energía almacenada, Moth-Poulsen pasa el combustible activado sobre un catalizador a base de cobalto. Las moléculas de cuadriciclano similares a Hyde luego vuelven a cambiar a su forma Jekyll, norbornadieno. La transformación libera grandes cantidades de calor, lo suficiente para elevar la temperatura del combustible en 63 grados centígrados (113 grados Fahrenheit).

Si el combustible comienza a temperatura ambiente (alrededor de 21 grados C o 70 grados F), se calienta rápidamente a alrededor de 84 grados C (183 grados F), lo suficientemente caliente como para calentar una casa u oficina.

"Podría usar esa energía térmica para su calentador de agua, su lavaplatos o su secadora de ropa", dice Grossman. "También podría haber muchas aplicaciones industriales". Moth-Poulsen dice que el calor a baja temperatura utilizado para cocinar, la esterilización, el blanqueo, la destilación y otras operaciones comerciales representa el 7 por ciento de todo el consumo de energía en la Unión Europea.

Un combustible térmico solar podría almacenarse en tanques sin aislamiento dentro de casas o fábricas, o tal vez canalizarse o transportarse entre granjas solares y ciudades. Muy poco del combustible o del catalizador está dañado por las reacciones, por lo que el sistema puede funcionar en un circuito cerrado, captando la energía solar y desprendiendo calor una y otra vez. "Lo hemos ejecutado a través de 125 ciclos sin ninguna degradación significativa", dice Moth-Poulsen.

CALOR SIN FUEGO

Moth-Poulsen ha calculado que la mejor variante de su combustible puede almacenar hasta 250 vatios-hora de energía por kilogramo. Libra por libra, eso es aproximadamente el doble de la capacidad de energía de las baterías Tesla Powerwall que algunos propietarios y empresas de servicios públicos ahora utilizan para almacenar la electricidad generada por los paneles solares.

"Estoy muy emocionado por lo que está haciendo Kasper", dice Grossman sobre la investigación. Después de un estallido de trabajo sobre los combustibles de norbornadieno en la década de 1970, dice, los químicos fueron bloqueados. Los combustibles siguieron descomponiéndose después de unos pocos ciclos. No mantuvieron su energía por mucho tiempo, y tuvieron que mezclarse con solventes tóxicos que diluyeron el combustible que agarra la energía. Moth-Poulsen "ha vuelto a esa molécula y está utilizando herramientas de última generación para solucionarlo", dice Grossman.

Los nuevos resultados, publicados en una serie de artículos científicos durante el año pasado, han llamado la atención de los inversores. Moth-Poulsen dice que numerosas compañías lo han contactado para discutir el potencial de comercialización.

DEL PROTOTIPO AL PRODUCTO.

A pesar de la promesa de los combustibles solares térmicos, quedan por delante años de desarrollo. "Hemos progresado mucho", dice Moth-Poulsen, "pero todavía hay mucho por resolver".

Un próximo paso crucial será desarrollar un solo combustible que combine las mejores características de las muchas variantes de combustible que ha desarrollado el equipo de Chalmers, que incluyen una larga vida útil, una alta densidad de energía y una buena capacidad de reciclaje.

Wei Feng, quien encabeza un grupo de investigación que trabaja con combustibles térmicos solares en la Universidad de Tianjin en China, señala que la operación sin disolventes es otro "gran desafío para la futura comercialización".

Los combustibles prototipo de Moth-Poulsen se fabrican a través de procesos industriales comunes y de agentes industriales ampliamente disponibles, incluidos los derivados del acetileno. Pero no está claro cuánto costaría una versión comercial del combustible.

Un factor importante en el costo será la eficiencia del combustible, que actualmente es bastante bajo. Los combustibles prototipo responden solo a las longitudes de onda más cortas de la luz solar , incluidos los rayos ultravioleta y azul, que representan solo el 5 por ciento de la energía solar disponible. Moth-Poulsen dice que está trabajando para extender la sensibilidad del combustible para incluir más espectro.

También apunta a romper su propio récord de un aumento de temperatura de 63 grados C Cuando se agrega ese calor al agua que ha sido precalentada a 40 grados C o más por los colectores solares convencionales, dice: "Eso es suficiente para hervir el agua en vapor". El vapor podría entonces impulsar las turbinas para generar electricidad. Pero con más ajustes en la estructura química, dice, "creo que podríamos impulsar [el aumento de la temperatura] a 80 grados C o más". Para la generación de electricidad, cuanto más caliente es mejor.

"Cuando empecé, en realidad solo había un grupo de investigación trabajando en este tipo de sistemas", recuerda Moth-Poulsen, de 40 años. Pero el progreso ha atraído a otros al desafío. "Ahora hay equipos en los EE. UU., En China, en Alemania, alrededor de 15 en todo el mundo", dice.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario