Avances en tecnologia: Fusion / Ordenadores cuanticos/ Transmisión inalambrica de energia

MIT-designed project achieves major advance toward fusion energy

It was a moment three years in the making, based on intensive research and design work: On Sept. 5, for the first time, a large high-temperature superconducting electromagnet was ramped up to a field strength of 20 tesla, the most powerful magnetic field of its kind ever created on Earth. That successful demonstration helps resolve the greatest uncertainty in the quest to build the world’s first fusion power plant that can produce more power than it consumes, according to the project’s leaders at MIT and startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS).

That advance paves the way, they say, for the long-sought creation of practical, inexpensive, carbon-free power plants that could make a major contribution to limiting the effects of global climate change.

“Fusion in a lot of ways is the ultimate clean energy source,” says Maria Zuber, MIT’s vice president for research and E. A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics. “The amount of power that is available is really game-changing.” The fuel used to create fusion energy comes from water, and “the Earth is full of water — it’s a nearly unlimited resource. We just have to figure out how to utilize it.”

Developing the new magnet is seen as the greatest technological hurdle to making that happen; its successful operation now opens the door to demonstrating fusion in a lab on Earth, which has been pursued for decades with limited progress. With the magnet technology now successfully demonstrated, the MIT-CFS collaboration is on track to build the world’s first fusion device that can create and confine a plasma that produces more energy than it consumes. That demonstration device, called SPARC, is targeted for completion in 2025.

“The challenges of making fusion happen are both technical and scientific,” says Dennis Whyte, director of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center, which is working with CFS to develop SPARC. But once the technology is proven, he says, “it’s an inexhaustible, carbon-free source of energy that you can deploy anywhere and at any time. It’s really a fundamentally new energy source.”

Whyte, who is the Hitachi America Professor of Engineering, says this week’s demonstration represents a major milestone, addressing the biggest questions remaining about the feasibility of the SPARC design. “It’s really a watershed moment, I believe, in fusion science and technology,” he says.

The sun in a bottle

Fusion is the process that powers the sun: the merger of two small atoms to make a larger one, releasing prodigious amounts of energy. But the process requires temperatures far beyond what any solid material could withstand. To capture the sun’s power source here on Earth, what’s needed is a way of capturing and containing something that hot — 100,000,000 degrees or more — by suspending it in a way that prevents it from coming into contact with anything solid.

That’s done through intense magnetic fields, which form a kind of invisible bottle to contain the hot swirling soup of protons and electrons, called a plasma. Because the particles have an electric charge, they are strongly controlled by the magnetic fields, and the most widely used configuration for containing them is a donut-shaped device called a tokamak. Most of these devices have produced their magnetic fields using conventional electromagnets made of copper, but the latest and largest version under construction in France, called ITER, uses what are known as low-temperature superconductors.

The major innovation in the MIT-CFS fusion design is the use of high-temperature superconductors, which enable a much stronger magnetic field in a smaller space. This design was made possible by a new kind of superconducting material that became commercially available a few years ago. The idea initially arose as a class project in a nuclear engineering class taught by Whyte. The idea seemed so promising that it continued to be developed over the next few iterations of that class, leading to the ARC power plant design concept in early 2015. SPARC, designed to be about half the size of ARC, is a testbed to prove the concept before construction of the full-size, power-producing plant.

Until now, the only way to achieve the colossally powerful magnetic fields needed to create a magnetic “bottle” capable of containing plasma heated up to hundreds of millions of degrees was to make them larger and larger. But the new high-temperature superconductor material, made in the form of a flat, ribbon-like tape, makes it possible to achieve a higher magnetic field in a smaller device, equaling the performance that would be achieved in an apparatus 40 times larger in volume using conventional low-temperature superconducting magnets. That leap in power versus size is the key element in ARC’s revolutionary design.

The use of the new high-temperature superconducting magnets makes it possible to apply decades of experimental knowledge gained from the operation of tokamak experiments, including MIT’s own Alcator series. The new approach, led by Zach Hartwig, the MIT principal investigator and the Robert N. Noyce Career Development Assistant Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering, uses a well-known design but scales everything down to about half the linear size and still achieves the same operational conditions because of the higher magnetic field.

A series of scientific papers published last year outlined the physical basis and, by simulation, confirmed the viability of the new fusion device. The papers showed that, if the magnets worked as expected, the whole fusion system should indeed produce net power output, for the first time in decades of fusion research.

Martin Greenwald, deputy director and senior research scientist at the PSFC, says unlike some other designs for fusion experiments, “the niche that we were filling was to use conventional plasma physics, and conventional tokamak designs and engineering, but bring to it this new magnet technology. So, we weren’t requiring innovation in a half-dozen different areas. We would just innovate on the magnet, and then apply the knowledge base of what’s been learned over the last decades.”

That combination of scientifically established design principles and

game-changing magnetic field strength is what makes it possible to

achieve a plant that could be economically viable and developed on a

fast track. “It’s a big moment,” says Bob Mumgaard, CEO of CFS. “We now

have a platform that is both scientifically very well-advanced, because

of the decades of research on these machines, and also commercially very

interesting. What it does is allow us to build devices faster, smaller,

and at less cost,” he says of the successful magnet demonstration.

Proof of the concept

Bringing that new magnet concept to reality required three years of intensive work on design, establishing supply chains, and working out manufacturing methods for magnets that may eventually need to be produced by the thousands.

“We built a first-of-a-kind, superconducting magnet. It required a lot of work to create unique manufacturing processes and equipment. As a result, we are now well-prepared to ramp-up for SPARC production,” says Joy Dunn, head of operations at CFS. “We started with a physics model and a CAD design, and worked through lots of development and prototypes to turn a design on paper into this actual physical magnet.” That entailed building manufacturing capabilities and testing facilities, including an iterative process with multiple suppliers of the superconducting tape, to help them reach the ability to produce material that met the needed specifications — and for which CFS is now overwhelmingly the world’s biggest user.

They worked with two possible magnet designs in parallel, both of which ended up meeting the design requirements, she says. “It really came down to which one would revolutionize the way that we make superconducting magnets, and which one was easier to build.” The design they adopted clearly stood out in that regard, she says.

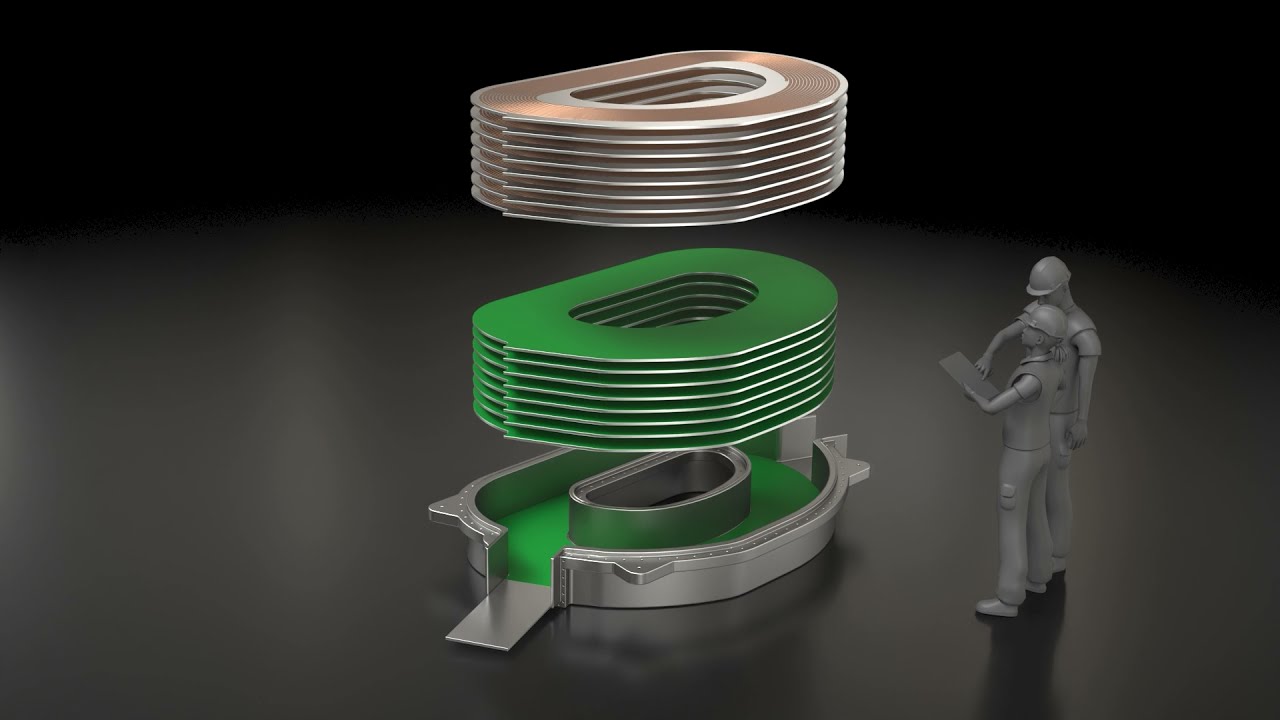

In this test, the new magnet was gradually powered up in a series of steps until reaching the goal of a 20 tesla magnetic field — the highest field strength ever for a high-temperature superconducting fusion magnet. The magnet is composed of 16 plates stacked together, each one of which by itself would be the most powerful high-temperature superconducting magnet in the world.

“Three years ago we announced a plan,” says Mumgaard, “to build a 20-tesla magnet, which is what we will need for future fusion machines.” That goal has now been achieved, right on schedule, even with the pandemic, he says.

Citing the series of physics papers published last year, Brandon Sorbom, the chief science officer at CFS, says “basically the papers conclude that if we build the magnet, all of the physics will work in SPARC. So, this demonstration answers the question: Can they build the magnet? It’s a very exciting time! It’s a huge milestone.”

The next step will be building SPARC, a smaller-scale version of the planned ARC power plant. The successful operation of SPARC will demonstrate that a full-scale commercial fusion power plant is practical, clearing the way for rapid design and construction of that pioneering device can then proceed full speed.

Zuber says that “I now am genuinely optimistic that SPARC can achieve net positive energy, based on the demonstrated performance of the magnets. The next step is to scale up, to build an actual power plant. There are still many challenges ahead, not the least of which is developing a design that allows for reliable, sustained operation. And realizing that the goal here is commercialization, another major challenge will be economic. How do you design these power plants so it will be cost effective to build and deploy them?”

Someday in a hoped-for future, when there may be thousands of fusion plants powering clean electric grids around the world, Zuber says, “I think we’re going to look back and think about how we got there, and I think the demonstration of the magnet technology, for me, is the time when I believed that, wow, we can really do this.”

The successful creation of a power-producing fusion device would be a tremendous scientific achievement, Zuber notes. But that’s not the main point. “None of us are trying to win trophies at this point. We’re trying to keep the planet livable.”

https://news.mit.edu/2021/MIT-CFS-major-advance-toward-fusion-energy-0908?fbclid=IwAR0ti7G3obJ5aNSyQwTGl6wm6A6QDG5UV86UQPVbmDQ_CoRHtzXyLOUIx7I

Validating the physics behind the new MIT-designed fusion experiment

Two and a half years ago, MIT entered into a research agreement with startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems to develop a next-generation fusion research experiment, called SPARC, as a precursor to a practical, emissions-free power plant.

Now, after many months of intensive research and engineering work, the researchers charged with defining and refining the physics behind the ambitious tokamak design have published a series of papers summarizing the progress they have made and outlining the key research questions SPARC will enable.

Overall, says Martin Greenwald, deputy director of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center and one of the project’s lead scientists, the work is progressing smoothly and on track. This series of papers provides a high level of confidence in the plasma physics and the performance predictions for SPARC, he says. No unexpected impediments or surprises have shown up, and the remaining challenges appear to be manageable. This sets a solid basis for the device’s operation once constructed, according to Greenwald.

Greenwald wrote the introduction for a set of seven research papers authored by 47 researchers from 12 institutions and published today in a special issue of the Journal of Plasma Physics. Together, the papers outline the theoretical and empirical physics basis for the new fusion system, which the consortium expects to start building next year.

SPARC is planned to be the first experimental device ever to achieve a “burning plasma” — that is, a self-sustaining fusion reaction in which different isotopes of the element hydrogen fuse together to form helium, without the need for any further input of energy. Studying the behavior of this burning plasma — something never before seen on Earth in a controlled fashion — is seen as crucial information for developing the next step, a working prototype of a practical, power-generating power plant.

Such fusion power plants might significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the power-generation sector, one of the major sources of these emissions globally. The MIT and CFS project is one of the largest privately funded research and development projects ever undertaken in the fusion field.

"The MIT group is pursuing a very compelling approach to fusion energy." says Chris Hegna, a professor of engineering physics at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, who was not connected to this work. "They realized the emergence of high-temperature superconducting technology enables a high magnetic field approach to producing net energy gain from a magnetic confinement system. This work is a potential game-changer for the international fusion program."

The SPARC design, though about twice the size as MIT’s now-retired Alcator C-Mod experiment and similar to several other research fusion machines currently in operation, would be far more powerful, achieving fusion performance comparable to that expected in the much larger ITER tokamak being built in France by an international consortium. The high power in a small size is made possible by advances in superconducting magnets that allow for a much stronger magnetic field to confine the hot plasma.

The SPARC project was launched in early 2018, and work on its first stage, the development of the superconducting magnets that would allow smaller fusion systems to be built, has been proceeding apace. The new set of papers represents the first time that the underlying physics basis for the SPARC machine has been outlined in detail in peer-reviewed publications. The seven papers explore the specific areas of the physics that had to be further refined, and that still require ongoing research to pin down the final elements of the machine design and the operating procedures and tests that will be involved as work progresses toward the power plant.

The papers also describe the use of calculations and simulation tools for the design of SPARC, which have been tested against many experiments around the world. The authors used cutting-edge simulations, run on powerful supercomputers, that have been developed to aid the design of ITER. The large multi-institutional team of researchers represented in the new set of papers aimed to bring the best consensus tools to the SPARC machine design to increase confidence it will achieve its mission.

The analysis done so far shows that the planned fusion energy output of the SPARC tokamak should be able to meet the design specifications with a comfortable margin to spare. It is designed to achieve a Q factor — a key parameter denoting the efficiency of a fusion plasma — of at least 2, essentially meaning that twice as much fusion energy is produced as the amount of energy pumped in to generate the reaction. That would be the first time a fusion plasma of any kind has produced more energy than it consumed.

The calculations at this point show that SPARC could actually achieve a Q ratio of 10 or more, according to the new papers. While Greenwald cautions that the team wants to be careful not to overpromise, and much work remains, the results so far indicate that the project will at least achieve its goals, and specifically will meet its key objective of producing a burning plasma, wherein the self-heating dominates the energy balance.

Limitations imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic slowed progress a bit, but not much, he says, and the researchers are back in the labs under new operating guidelines.

Overall, “we’re still aiming for a start of construction in roughly June of ’21,” Greenwald says. “The physics effort is well-integrated with the engineering design. What we’re trying to do is put the project on the firmest possible physics basis, so that we’re confident about how it’s going to perform, and then to provide guidance and answer questions for the engineering design as it proceeds.”

Many of the fine details are still being worked out on the machine design, covering the best ways of getting energy and fuel into the device, getting the power out, dealing with any sudden thermal or power transients, and how and where to measure key parameters in order to monitor the machine’s operation.

So far, there have been only minor changes to the overall design. The diameter of the tokamak has been increased by about 12 percent, but little else has changed, Greenwald says. “There’s always the question of a little more of this, a little less of that, and there’s lots of things that weigh into that, engineering issues, mechanical stresses, thermal stresses, and there’s also the physics — how do you affect the performance of the machine?”

The publication of this special issue of the journal, he says, “represents a summary, a snapshot of the physics basis as it stands today.” Though members of the team have discussed many aspects of it at physics meetings, “this is our first opportunity to tell our story, get it reviewed, get the stamp of approval, and put it out into the community.”

Greenwald says there is still much to be learned about the physics of burning plasmas, and once this machine is up and running, key information can be gained that will help pave the way to commercial, power-producing fusion devices, whose fuel — the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium — can be made available in virtually limitless supplies.

The details of the burning plasma “are really novel and important,” he says. “The big mountain we have to get over is to understand this self-heated state of a plasma.”

"The analysis presented in these papers will provide the world-wide fusion community with an opportunity to better understand the physics basis of the SPARC device and gauge for itself the remaining challenges that need to be resolved," says George Tynan, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California at San Diego, who was not connected to this work. "Their publication marks an important milestone on the road to the study of burning plasmas and the first demonstration of net energy production from controlled fusion, and I applaud the authors for putting this work out for all to see."

Overall, Greenwald says, the work that has gone into the analysis presented in this package of papers “helps to validate our confidence that we will achieve the mission. We haven’t run into anything where we say, ‘oh, this is predicting that we won’t get to where we want.” In short, he says, “one of the conclusions is that things are still looking on-track. We believe it’s going to work.”

https://news.mit.edu/2020/physics-fusion-studies-0929?fbclid=IwAR0FHbHybvdrOchn27CiJjN3I2lQYxArEJ9E4t2melZP2jnjnnctO0f30_c

China's New Quantum Computer Has 1 Million Times the Power of Google's

And they say it's the world's fastest.

t appears a quantum computer rivalry is growing between the U.S. and China.

Physicists in China claim they've constructed two quantum computers with performance speeds that outrival competitors in the U.S., debuting a superconducting machine, in addition to an even speedier one that uses light photons to obtain unprecedented results, according to a recent study published in the peer-reviewed journals Physical Review Letters and Science Bulletin.

China has exaggerated the capabilities of its technology before, but such soft spins are usually tagged to defense tech, which means this new feat could be the real deal.

China's quantum computers still make a lot of errors

The supercomputer, called Jiuzhang 2, can calculate in a single millisecond a task that the fastest conventional computer in the world would take a mind-numbing 30 trillion years to do. The breakthrough was revealed during an interview with the research team, which was broadcast on China's state-owned CCTV on Tuesday, which could make the news suspect. But with two peer-reviewed papers, it's important to take this seriously. Pan Jianwei, lead researcher of the studies, said that Zuchongzhi 2, which is a 66-qubit programmable superconducting quantum computer is an incredible 10 million times faster than Google's 55-qubit Sycamore, making China's new machine the fastest in the world, and the first to beat Google's in two years.

https://interestingengineering.com/chinas-new-quantum-computer-has-1-million-times-the-power-of-googles?fbclid=IwAR1svs7zQTyYQi93t2mmTd6zBOd1IkyFWP90gOadVzyNmbhuVoi8FQqYCkY

El láser que nos acerca a un nuevo tipo de fusión nuclear

Investigadores de la fuerza naval de Estados Unidos están desarrollando un láser de fluoruro de argón que podría dar pie a plantas de energía de fusión más pequeñas y más baratas

El Laboratorio de Investigación Naval de Estados Unidos (NRL) está desarrollando un láser de fluoruro de argón que, según sus creadores, puede alcanzar la energía y la potencia necesarias para llevar a cabo la fusión nuclear. Este nuevo método promete también reducir el tamaño y el coste de este tipo de centrales haciéndolas todavía más viables.

:format(jpg)/https://f.elconfidencial.com/original/439/3f7/baf/4393f7baf396f9b1f979296caea12aea.jpg)

Uno de los mayores retos que tiene por delante la fusión nuclear para poder cumplir con el sueño de la energía barata e infinita está en conseguir que el proceso no necesite más energía de la que genera. En eso están los investigadores del ITER, un gigantesco reactor que se está construyendo en el sur de Francia, los de la canadiense General Fusión, que cuentan con el soporte financiero de Jeff Bezos o los de la coreana KSTAR que ya ha conseguido mantener la fusión nuclear a 100 millones de grados centígrados durante 20 segundos.

Todos estos reactores utilizan diversos sistemas de imanes para conseguir la unión de los núcleos de los átomos de hidrógeno. Pero el método creado por los investigadores de la fuerza naval norteamericana se basa en otro principio, el de confinamiento inercial. Este sistema utiliza rayos láser para conseguir alcanzar las altas densidades y los 100 millones de grados centígrados necesarios para iniciar las reacciones de fusión.

:format(jpg)/https://f.elconfidencial.com/original/43c/5ba/007/43c5ba00703dc49612754a717b01e4b8.jpg)

:format(jpg)/https://f.elconfidencial.com/original/43c/5ba/007/43c5ba00703dc49612754a717b01e4b8.jpg)

"El láser de fluoruro de argón podría permitir el desarrollo y la construcción de centrales de fusión mucho más pequeñas y de menor coste", dijo Steve Obenschain, investigador del NRL y uno de los autores del estudio publicado en la revista 'The Royal Society' donde se detalla su descubrimiento. "Esto aceleraría el despliegue de esta atractiva fuente de energía con suficientes reservas de combustible disponibles como para durar miles de años".

Cómo funciona

El método de confinamiento inercial consiste en aplicar varios rayos láser a una pequeña pelota de combustible nuclear compuesto por deuterio o tritio, que son isótopos del hidrógeno. Con el impacto de los láseres, la pelota de combustible, que puede tener el tamaño aproximado de un garbanzo pedrosillano, se calienta y se comprime en una fracción de segundo hasta tal punto que los átomos de hidrógeno implosionan, se fusionan y liberan enormes cantidades de energía.

Este verano un sistema similar, creado por el National Ignition Facility (NIF) de EEUU, consiguió crear casi tanta energía con la fusión como la empleada por su dispositivo de 192 rayos láser. El NIF fue capaz de producir 1,3 megajulios de energía de fusión demostrando la viabilidad de este sistema.

:format(jpg)/https://f.elconfidencial.com/original/f34/382/f1c/f34382f1cc7410de09f2475c4e131394.jpg)

:format(jpg)/https://f.elconfidencial.com/original/f34/382/f1c/f34382f1cc7410de09f2475c4e131394.jpg)

Según las simulaciones realizadas por el NRL, la luz ultravioleta profunda del ArF permite generar ganancia energética empleando una energía de láser mucho más baja de lo que se creía posible hasta ahora. Los científicos afirman que el rendimiento podría multiplicarse por cien y conseguir una eficiencia del 16%, cuatro puntos por encima del siguiente láser más eficiente, el de fluoruro de criptón.

"El resultado del NIF es impresionante y pone de manifiesto la necesidad de mirar hacia adelante para ver qué tecnologías láser acelerarán el progreso futuro. La tecnología del láser ArF del NRL ofrece un camino hacia una ganancia y un rendimiento de la fusión mucho más elevados", afirma Obenschain.

Qué hace falta para que esté operativo

Obenschain reconoce que este sistema de láseres ArF todavía requiere trabajo y una importante inversión para alcanzar el rendimiento necesario para hacerlo viable a nivel comercial. Para el investigador, todavía falta mejorar la precisión, la tasa de repetición y la fiabilidad de los mil millones de disparos necesarios para poner en marcha una central eléctrica que se pueda conectar a la red eléctrica. Los investigadores aseguran que los planes para los próximos experimentos ya están en marcha y se espera que tengan lugar en los próximos meses.

https://www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/novaceno/2021-10-27/nuevo-laser-acerca-nuevo-tipo-fusion-nuclear_3313487/?utm_source=Facebook&utm_medium=Social%20Adv&utm_campaign=Repesca%20Mobile%20Novaceno%20Copy&utm_content=10159807602476926%7CAdSet%201%7CMob_AudienceNetwork%7C-%7C-&fbclid=IwAR3hJOHBPOf5mUjF_sm-wXGHnCj5JDiLH3nQzsY1wE-xtuLncxqXdRXgFkM

La transmisión inalámbrica de energía es posible: hace funcionar una estación 5G con láseres

La energía inalámbrica tiene el potencial de ser muy útil, pero el alcance es un gran obstáculo. En un nuevo proyecto de prueba de concepto, Ericsson y PowerLight Technologies han demostrado una técnica llamada optical beaming, que utiliza un láser para transmitir energía a una estación base 5G portátil.

La experiencia de la mayoría de la gente con la energía inalámbrica es para cargar dispositivos como teléfonos, relojes o auriculares, pero eso sigue requiriendo que se coloquen en una almohadilla, lo que limita su utilidad. Los laboratorios están experimentando con sistemas más grandes que pueden cargar dispositivos en cualquier lugar de una habitación, pero ¿qué pasa con la transmisión de electricidad a largas distancias en el exterior?

PowerLight lleva años desarrollando la tecnología necesaria para ello, y ahora la ha demostrado con una prueba de concepto en colaboración con la empresa de telecomunicaciones Ericsson. El sistema consta de dos componentes principales, un transmisor y un receptor, que pueden estar separados por cientos o miles de metros.

El sistema no envía electricidad directamente, como una bobina de Tesla, sino que la electricidad en el extremo del transmisor se utiliza para producir un potente haz de luz y enviarlo hacia el receptor, que lo capta mediante una matriz fotovoltaica especializada. Éste, a su vez, convierte los fotones entrantes en electricidad, para alimentar cualquier dispositivo al que esté conectado.

Figura 1. Un diagrama que ilustra la tecnología de transmisión inalámbrica de energía.

Aunque pueda parecer peligroso tener un haz de luz de alta intensidad al aire libre, existen medidas de seguridad. El propio haz está rodeado por un "cilindro" más amplio de sensores que detectan cuando se acerca algo y apagan el haz en un milisegundo. Es tan rápido que interrupciones fugaces como las de los pájaros no afectarían al servicio, pero hay una batería de reserva en el extremo del receptor para cubrir cualquier posible interrupción a largo plazo.

En este caso, el sistema PowerLight alimentaba una de las estaciones radiobase 5G de Ericsson, que no estaba conectada a ninguna otra fuente de energía. El sistema suministró 480 vatios a una distancia de 300 m, pero el equipo afirma que la tecnología ya debería ser capaz de enviar 1.000 vatios a más de 1 km, con margen de ampliación en futuras pruebas.

Alimentar estas unidades 5G de forma inalámbrica podría hacerlas más portátiles, lo que permitiría desplegarlas en lugares temporales de mayor demanda, como festivales y eventos, o durante catástrofes en las que se hayan interrumpido otras infraestructuras.

La tecnología de transmisión óptica de PowerLight podría utilizarse también en muchas otras aplicaciones, como la recarga de vehículos eléctricos, el ajuste de la red eléctrica sobre la marcha e incluso en futuras misiones espaciales.

Pero no es la única empresa que trabaja con objetivos similares. El año pasado, la empresa neozelandesa Emrod presentó su propia visión para la transmisión de energía a larga distancia, pero en lugar de luz y células fotovoltaicas, transmite energía por microondas entre antenas.

Los prototipos de Emrod han transmitido hasta ahora unos 2 kilovatios de energía a más de 40 m, y la empresa afirma que debería ser capaz de ampliar la escala para enviar mucha más energía a decenas de kilómetros.

Entre todos, la transmisión inalámbrica de energía podría convertirse en una parte fundamental de las redes eléctricas en las próximas décadas.

- https://www.worldenergytrade.com/energias-alternativas/investigacion/la-transmision-inalambrica-de-energia-es-posible-hace-funcionar-una-estacion-5g-con-laseres?fbclid=IwAR0LBpkeMBNBHUi1WFZcPSkgU2n2xK0jGFTO39nR2-WnoAoYVB9mp5DTa_Y

China alcanza la corona de la supremacía cuántica

China ostenta ya el liderazgo indiscutible en la supremacía cuántica con dos ordenadores, uno que usa la luz y otro circuitos superconductores, que realizan proezas de cálculo inalcanzables para la computación tradicional.

China ha desarrollado dos ordenadores cuánticos diferentes, uno que usa la luz y otro circuitos superconductores, y obtenido una potencia de cálculo inalcanzable para la computación tradicional, según se explica en dos artículos publicados en Physical Review Letters.

Eso significa que este doble sistema de computación cuántica otorga a China la capacidad de resolver problemas prácticos que no se pueden implementar en ordenadores convencionales, destaca al respecto PhysicsWorld.

Con este resultado, China ya es mucho más que una potencia económica: junto a sus desarrollos energéticos con el sol artificial, también ha entrado con fuerza en la «carrera espacial» del siglo XXI, con diferentes proyectos orientados a Marte y la Luna.

Tema relacionado: El sol artificial chino se pone en cabeza de la carrera de la fusión nuclear

Pioneros en información cuántica

Los nuevos ordenadores cuánticos han sido desarrollados por dos grupos del Laboratorio Nacional de Ciencias Físicas de Hefei, de la Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de China, dirigidos por el profesor Jian-Wei Pan, cuya labor ha sido destacada en el pasado, tanto por la revista Nature como por Science, como pionero en la ciencia de la información cuántica experimental.

El pasado julio, China anunció que había alcanzado la supremacía cuántica con un superordenador llamado Zuchongzhi, capaz de realizar operaciones mucho más rápido que la computadora cuántica de Google.

Zuchongzhi completó un cálculo complejo en algo más de una hora, haciéndolo unas 60.000 veces más deprisa que un ordenador clásico: utilizando 56 cúbits, resolvió en solo 1,2 horas una tarea que a un superordenador clásico le llevaría ocho años.

Dos nuevos ordenadores cuánticos

China emerge ahora con un nuevo ordenador cuántico, al que denomina Zuchongzhi 2.1, que usa 66 cúbits y es 10 millones de veces más rápido que el superordenador más rápido actual: su complejidad de cálculo es más de 1 millón de veces mayor que el procesador Sycamore de Google.

También emerge con otro superordenador cuántico, al que denomina Jiuzhang 2.0, que usa la luz para procesar información, en vez de los circuitos superconductores que sustentan a Zuchongzhi 2.1.

«Jiuzhang 2.0», con 113 fotones que transmiten cúbits, es un septillón de veces más potente: puede resolver en un milisegundo una operación que el ordenador más rápido del mundo tardaría 30 billones de años.

Este segundo desarrollo representa también toda una proeza ante la versión anterior de este mismo sistema de computación cuántica basada en la luz, el «Jiuzhang», presentado a finales de 2020 y con el cual se utilizaron 76 fotones transmisores de cúbits.

Supremacía cuántica

Con estos desarrollos, China consolida su ventaja cuántica global y confirma que los ordenadores cuánticos son mucho más potentes y eficaces que los ordenadores clásicos para resolver problemas críticos.

Los ordenadores clásicos se basan en el sistema binario, en el que cada símbolo constituye un bit, la unidad mínima de información de este sistema, que solo puede tener dos valores (cero o uno).

Estos ordenadores clásicos han conseguido aumentar su potencia a través de los superordenadores, que aparecieron en los años 70 del siglo pasado.

Estos superordenadores, más conocidos como ordenadores de alto rendimiento, basan sus extraordinarias capacidades (medidas en petaflops) en la suma de poderosos ordenadores binarios unidos entre sí para aumentar su potencia de trabajo y rendimiento.

Otro universo

La informática cuántica pertenece a otro universo: usa una unidad básica de información completamente diferente y superior llamaba cúbit.

El cúbit, a diferencia del bit, puede tomar varios valores a la vez, es decir, manifiesta un sistema cuántico con dos estados propios simultáneos.

Mientras que el bit adopta valores de 0 o 1 en grupos de 8,16,32 o 64 bits, la medida en cúbits puede estar en ambos estados de 0 y 1 de forma simultánea, lo que le otorga la capacidad de realizar operaciones inalcanzables para la computación binaria.

La supremacía cuántica se alcanza cuando se demuestra que un ordenador basado en cúbits puede resolver algo que no está al alcance de ordenadores binarios, aunque sean muy sofisticados.

Supremacía doble

Aunque se ha afirmado en el pasado que la supremacía cuántica ya se ha alcanzado, y se convirtió en un campo de batalla entre IBM y Google, China ha adelantado a ambos con desarrollos mucho más potentes que, según la revista Physics, le otorgan sin lugar a duda la supremacía cuántica real y verificada.

Y no solo eso, sino que lo ha conseguido siguiendo dos caminos diferentes y paralelos que fortifican su supremacía: el de la luz y el de los circuitos superconductores.

Physics destaca que es muy difícil que algoritmos y ordenadores clásicos puedan mejorar las ventajas cuánticas de China, por lo que podemos decir que el debate sobre si realmente existe la supremacía cuántica ha concluido.

¿Supremacía útil?

Y concluye la revista: dado que las máquinas cuánticas resuelven problemas tan grandes e impresionantes de una manera que supera con creces a los simuladores clásicos, ¿podríamos usar estos ordenadores cuánticos para resolver problemas computacionales útiles?

Los investigadores han afirmado que estos ordenadores cuánticos pueden abordar problemas importantes, en particular en el campo de la química cuántica, pero aún no se ha informado de ninguna demostración experimental convincente, finaliza Physics.

Referencias

Strong Quantum Computational Advantage Using a Superconducting Quantum Processor. Yulin Wu et al.Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 180501. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.180501

Phase-Programmable Gaussian Boson Sampling Using Stimulated Squeezed Light. Han-Sen Zhong et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 180502. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.180502

https://tendencias21.levante-emv.com/china-alcanza-la-corona-de-la-supremacia-cuantica.html?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=dogtrack

China may be secretly sitting on the two most powerful supercomputers in the world

China is supposedly sitting on two systems capable of breaching the exascale barrier

By

The exascale barrier

Multiple supercomputing institutions in China have built machines that have already breached the landmark exascale barrier in behind-closed-doors testing, reports suggest.

According to Next Platform, which says it has the information on “outstanding authority”, a machine at the National Supercomputing Center in Wuxi (called Sunway Oceanlite) recorded a peak score of 1.3 exaFLOPS by the LINPACK benchmark as early as March this year.

Another system, the Tianhe-3, is said to have achieved an almost identical score, but it’s unclear precisely when testing took place in this instance.

Although

little is known about the architecture of the Wuxi machine, the

Tianhe-3 is known to be based on silicon from Chinese company Phytium,

boosted by a matrix accelerator.

The record for world’s fastest supercomputer is currently held by a Japanese machine, Fugaku. It snatched the crown in June 2020 with a score of 416 petaFLOPs (or 0.416 exaFLOPs), almost three times the peak performance of the previous leader, IBM Summit.

Since then, Fugaku’s lead has widened with the addition of a further 330,000 cores, boosting the performance to 442 petaFLOPS. However, if reports are accurate, both Tianhe-3 and Sunway Oceanlite outstrip the current leader by almost a factor of three.

The arrival of exascale supercomputers is expected to unlock a host of opportunities in a variety of sectors. For example, this level of performance will accelerate time to discovery in fields such as clinical medicine and genomics, which require vast amounts of computing power to conduct molecular modelling and genome sequencing.

Artificial

intelligence (AI) is another cross-disciplinary domain that will be

transformed with the arrival of exascale computing. The ability to

analyze ever-larger datasets will improve the ability of AI models to

make accurate forecasts that could be applied in virtually any context,

from cybersecurity to ecommerce, manufacturing, logistics, banking and more.

As the US and China battle for AI supremacy, the arrival of two exascale-capable systems in China before the US can debut its own upcoming exascale machine (“Frontier”), will be a kick in the teeth for the Biden administration, especially given they are built on Chinese silicon.

It’s unclear why China did not submit its machines to the bi-annual Top 500 supercomputer rankings earlier this year, but the geopolitical climate almost certainly has something to do with it. The next edition of the rankings is due to be published next month.

If you’re after a powerful device for your desktop, check out our lists of the best workstations, best mobile workstations and best video editing computers.

https://www.techradar.com/news/china-may-be-secretly-sitting-on-the-two-most-powerful-supercomputers-in-the-world?fbclid=IwAR1WubuY53GK0ngCJ_ptrWFyil3bDMXbdL-1s6QbRLePX5XY55iuWVlFbqs

Chinese researchers achieve quantum advantage in two mainstream routes

Quantum computer firm Rigetti to go public via $1.5b offering

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202110/1235748.shtml?id=11

China sees breakthroughs in quantum technology, yet faces challenges

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1235231.shtml?id=11

World-First Quantum Research Breakthrough Allows for Full Spin Qubit Control

Yet another key obstacle on the road to quantum has been conquered.

Otro obstáculo clave en el camino a la cuántica ha sido conquistado. Un equipo de investigación con la Universidad de Copenhague de Dinamarca ha diseñado el primer sistema de computación cuántica del mundo que permite el funcionamiento simultáneo de todos sus qubits sin amenazar la coherencia cuántica. La investigación está siendo aclamada como un gran avance, eliminando uno de los obstáculos clave restantes para la escalada cuántica y su eventual despliegue convencional.

https://www.tomshardware.com/news/quantum-computing-breakthrough-qubit-control?fbclid=IwAR07xg7Exi4ct8JPiY9VjXcQfrkUGONygKvE2Fg7nDLt0HNmjIJzLYVUiK8

China’s Climate Goals Hinge on a $440 Billion Nuclear Buildout

China is planning at least 150 new reactors in the next 15 years, more than the

rest of the world has built in the past 35.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario