El coronavirus no fue diseñado en un laboratorio.

Así es como lo sabemos.

The coronavirus was not engineered in a lab. Here's how we know.

Mitos para dejar en cuarentena

-

Editor's note: On April 16, news came

out that the U.S. government said it was investigating the possibility

that the novel coronavirus may have somehow escaped from a lab, though

experts still think the possibility that it was engineered is unlikely.

This Live Science report explores the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

As the novel coronavirus causing COVID-19 spreads across the globe, with cases surpassing 284,000 worldwide today (March 20), misinformation is spreading almost as fast.

One

persistent myth is that this virus, called SARS-CoV-2, was made by

scientists and escaped from a lab in Wuhan, China, where the outbreak

began.

A new analysis of SARS-CoV-2 may finally put that

latter idea to bed. A group of researchers compared the genome of this

novel coronavirus with the seven other coronaviruses

known to infect humans: SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2, which can cause

severe disease; along with HKU1, NL63, OC43 and 229E, which typically

cause just mild symptoms, the researchers wrote March 17 in the journal Nature Medicine.

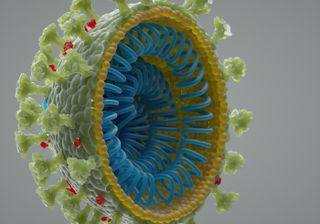

Viruses like the novel coronavirus are shells holding genetic material.

(Image: © Andriy Onufriyenko/Getty Images)

"Our

analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a

purposefully manipulated virus," they write in the journal article.

Kristian

Andersen, an associate professor of immunology and microbiology at

Scripps Research, and his colleagues looked at the genetic template for

the spike proteins that protrude from the surface of the virus. The coronavirus uses these spikes

to grab the outer walls of its host's cells and then enter those cells.

They specifically looked at the gene sequences responsible for two key

features of these spike proteins: the grabber, called the

receptor-binding domain, that hooks onto host cells; and the so-called

cleavage site that allows the virus to open and enter those cells.

That analysis showed that the "hook" part of the spike had evolved to target a receptor on the outside of human cells called ACE2,

which is involved in blood pressure regulation. It is so effective at

attaching to human cells that the researchers said the spike proteins

were the result of natural selection and not genetic engineering.

Here's

why: SARS-CoV-2 is very closely related to the virus that causes severe

acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which fanned across the globe nearly

20 years ago. Scientists have studied how SARS-CoV differs from

SARS-CoV-2 — with several key letter changes in the genetic code. Yet in

computer simulations, the mutations in SARS-CoV-2 don't seem to work

very well at helping the virus bind to human cells. If scientists had

deliberately engineered this virus, they wouldn't have chosen mutations

that computer models suggest won't work. But it turns out, nature is

smarter than scientists, and the novel coronavirus found a way to mutate

that was better — and completely different— from anything scientists

could have created, the study found.

Another

nail in the "escaped from evil lab" theory? The overall molecular

structure of this virus is distinct from the known coronaviruses and

instead most closely resembles viruses found in bats and pangolins that had been little studied and never known to cause humans any harm.

"If

someone were seeking to engineer a new coronavirus as a pathogen, they

would have constructed it from the backbone of a virus known to cause

illness," according to a statement from Scripps.

Where

did the virus come from? The research group came up with two possible

scenarios for the origin of SARS-CoV-2 in humans. One scenario follows

the origin stories for a few other recent coronaviruses that have

wreaked havoc in human populations. In that scenario, we contracted the

virus directly from an animal — civets in the case of SARS and camels in

the case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). In the case of

SARS-CoV-2, the researchers suggest that animal was a bat, which

transmitted the virus to another intermediate animal (possibly a

pangolin, some scientists have said) that brought the virus to humans.

In

that possible scenario, the genetic features that make the new

coronavirus so effective at infecting human cells (its pathogenic

powers) would have been in place before hopping to humans.

In

the other scenario, those pathogenic features would have evolved only

after the virus jumped from its animal host to humans. Some

coronaviruses that originated in pangolins have a "hook structure" (that

receptor binding domain) similar to that of SARS-CoV-2. In that way, a

pangolin either directly or indirectly passed its virus onto a human

host. Then, once inside a human host, the virus could have evolved to

have its other stealth feature — the cleavage site that lets it easily

break into human cells. Once it developed that capacity, the researchers

said, the coronavirus would be even more capable of spreading between

people.

Advertisement

All

of this technical detail could help scientists forecast the future of

this pandemic. If the virus did enter human cells in a pathogenic form,

that raises the probability of future outbreaks. The virus could still

be circulating in the animal population and might again jump to humans,

ready to cause an outbreak. But the chances of such future outbreaks are

lower if the virus must first enter the human population and then

evolve the pathogenic properties, the researchers said.

Coronavirus science and news

- Coronavirus in the US: Map & cases

- What are the symptoms?

- How deadly is the new coronavirus?

- How long does virus last on surfaces?

- Is there a cure for COVID-19?

- How does it compare with seasonal flu?

- How does the coronavirus spread?

- Can people spread the coronavirus after they recover?

- The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth

- 28 Devastating Infectious Diseases

- 11 Surprising Facts About the Respiratory System

https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-not-human-made-in-lab.html?fbclid=IwAR2PWNv7FGMCYYixDbKUGLTKDi21R5aMG1BAelyPxRC8t2b_-XgcqkcBubc

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario