Una

investigación biológica generalmente empieza con una observación, esto

es, con algo que llama la atención del biólogo. Por ejemplo, un biólogo

que estudia el cáncer puede notar que cierto tipo de cáncer no responde a

la quimioterapia y preguntarse por qué pasa eso. Una ecóloga marina, al

observar que los arrecifes de coral de su lugar de estudio se decoloran

(se vuelven blancos), puede empezar una investigación para entender las

causas de ese fenómeno.

¿Qué hacen los biólogos para dar seguimiento a esas observaciones? ¿De qué manera puedes

tú dar seguimiento a tus observaciones del mundo natural? En este artículo analizaremos el

método científico, un método lógico para la resolución de problemas usado por biólogos y muchos otros científicos.

El método científico

En

los fundamentos de la biología y otras ciencias se encuentra un método

de resolución de problemas llamado método científico. El

método científico tiene cinco pasos básicos (y un paso más de "retroalimentación"):

- Se hace una observación

- Se plantea una pregunta

- Se formula una hipótesis o explicación que pueda ponerse a prueba

- Se realiza una predicción con base en la hipótesis

- Se pone a prueba la predicción

- Se repite el proceso: se utilizan los resultados para formular nuevas hipótesis o predicciones.

El

método científico se usa en todas las ciencias (entre ellas, la

química, física, geología y psicología). Los científicos en estos campos

hacen diferentes preguntas y realizan distintas pruebas, sin embargo,

usan el mismo método para encontrar respuestas lógicas y respaldadas por

evidencia.

Ejemplo del método científico: no se tuesta el pan

Acerquémonos intuitivamente al método científico aplicando sus pasos a la resolución de un problema cotidiano.

1. Haz una observación

Supongamos que tienes dos rebanadas de pan, las pones en el tostador y presionas el botón. Sin embargo, tu pan no se tuesta.

- Observación: el tostador no tuesta.

2. Plantea una pregunta

¿Por qué no se tostó mi pan?

- Pregunta: ¿porqué mi tostador no tuesta?

3. Elabora una hipótesis

Una

hipótesis es

una respuesta posible a una pregunta, que de alguna manera puede

ponerse a prueba. Por ejemplo, nuestra hipótesis en este caso sería que

el tostador no funcionó porque el enchufe tomacorriente está

descompuesto.

- Hipótesis: tal vez el enchufe está descompuesto.

Esta

hipótesis no es necesariamente la respuesta correcta, sino una posible

explicación que podemos comprobar para ver si es correcta o si

necesitamos proponer otra.

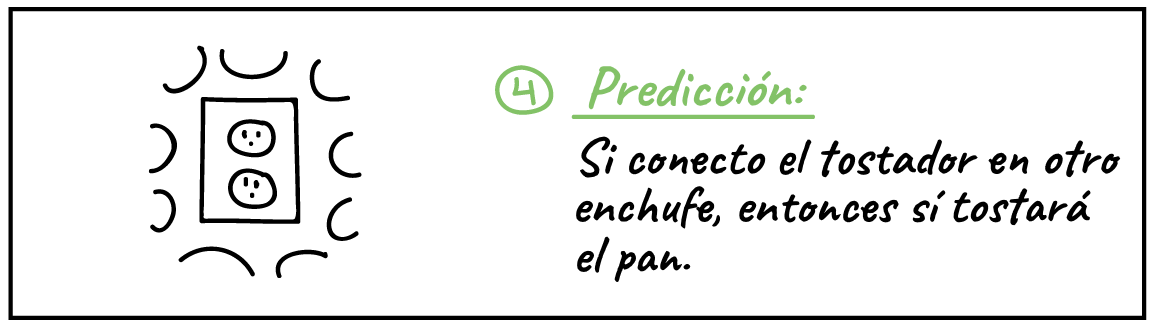

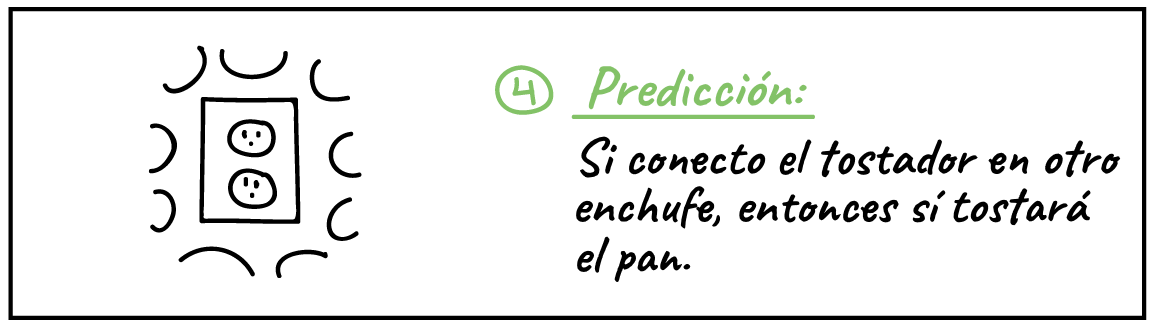

4. Haz predicciones

Una

predicción es un resultado que esperaríamos obtener si la hipótesis es

correcta. En este caso, podríamos predecir que si el enchufe de

corriente está descompuesto, entonces conectar el tostador en otro

enchufe de corriente debe solucionar el problema.

- Predicción: si conecto el tostador en otro enchufe, entonces sí tostará el pan.

5. Pon a prueba las predicciones

Para

probar la hipótesis, necesitamos observar o realizar un experimento

asociado con la predicción. En este caso, por ejemplo, podríamos

conectar el tostador en otro enchufe y ver si funciona.

- Prueba de la predicción: conecta el tostador en otro enchufe y vuelve a intentar.

- Si el tostador sí funciona, entonces la hipótesis es viable, y es probable que fuera correcta.

- Si el tostador no funciona, entonces la hipótesis no es viable, y es probable que fuera incorrecta.

Los

resultados del experimento pueden apoyar o contradecir (oponerse) la

hipótesis. Los resultados que la respaldan no prueban de manera

contundente que es correcta, pero sí que es muy probable que lo sea. Por

otro lado, si los resultados contradicen la hipótesis, probablemente

esta no sea correcta. A menos que hubiera un defecto en el experimento

(algo que siempre debemos considerar), un resultado contradictorio

significa que podemos descartar la hipótesis y proponer una nueva.

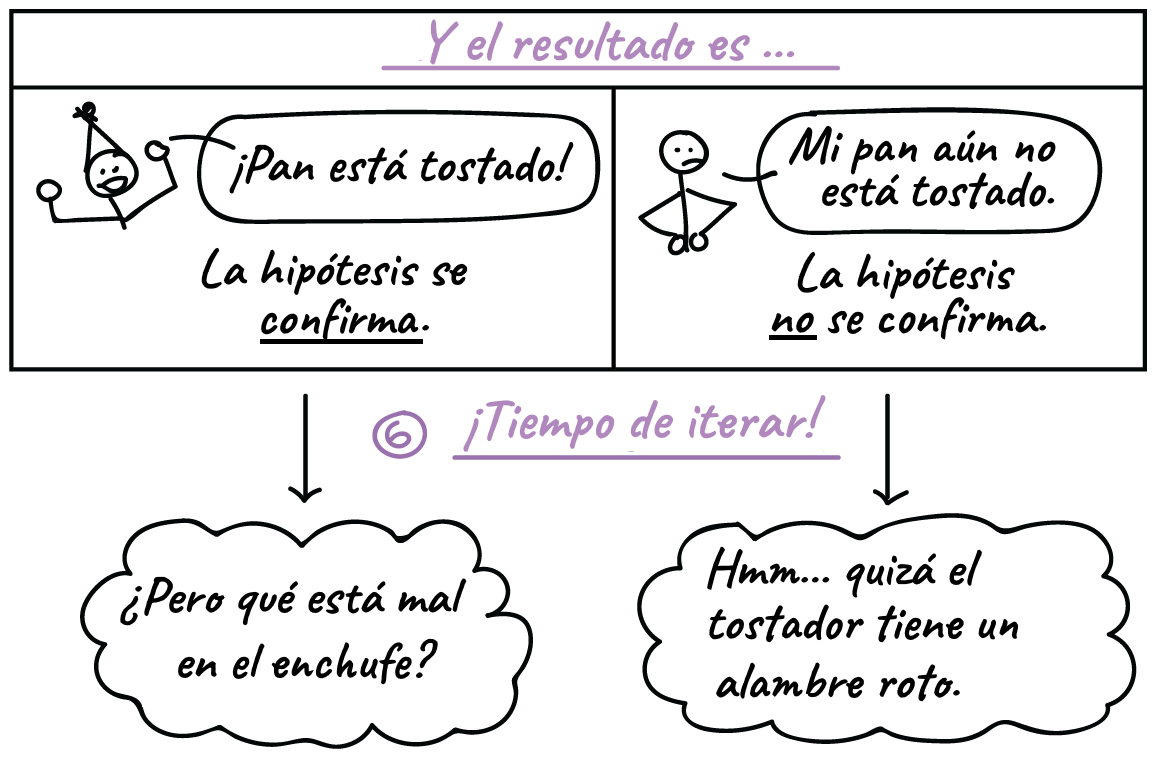

6. Repite

El

último paso del método científico es reflexionar sobre nuestros

resultados y utilizarlos para guiar nuestros siguientes pasos.

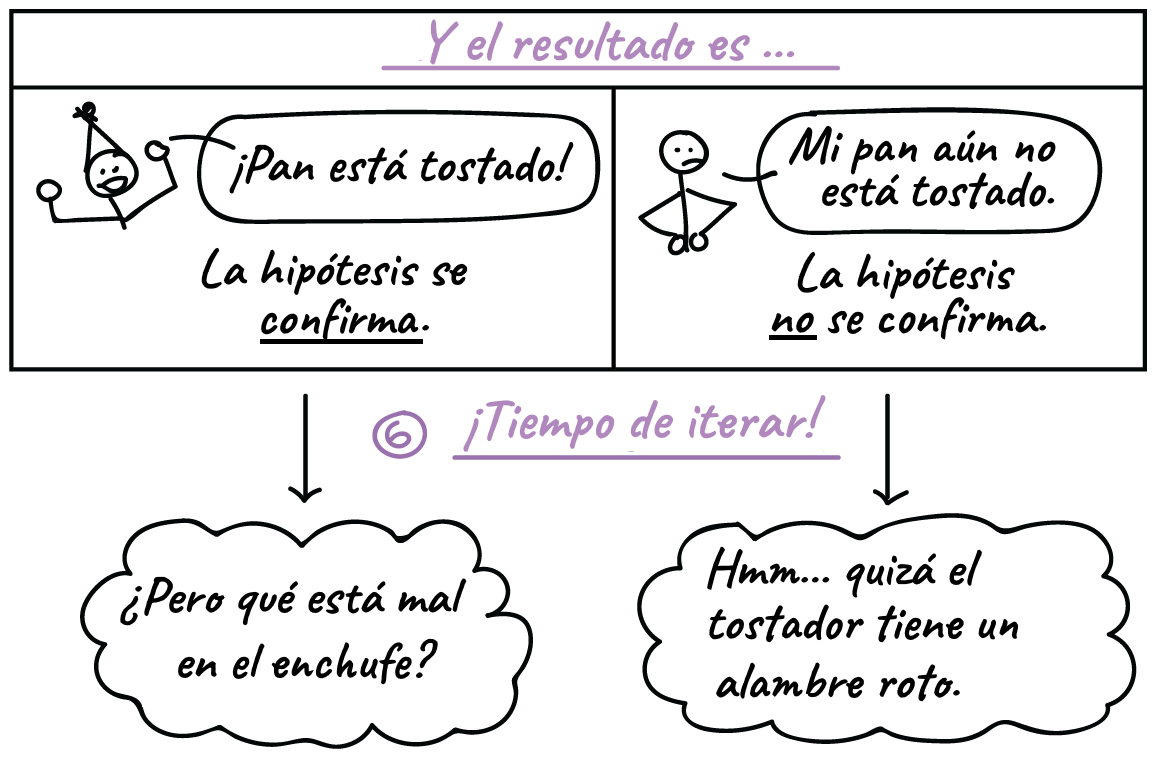

Y el resultado es:

Panel izquierdo: ¡mi pan se tuesta! La hipótesis se respalda. Panel derecho: mi pan aún no tuesta. La hipótesis no se respalda.

- ¡Tiempo de repetir!

Panel

izquierdo (en caso que la hipótesis se respalde): ¿pero qué falla en el

enchufe? Panel derecho (en caso que la hipótesis no se respalde): eh...

quizá el tostador tiene algún alambre roto.

- Si la

hipótesis fue respaldada, podríamos realizar otras pruebas para

confirmarla, o bien revisarla para que sea más específica. Por ejemplo,

podríamos investigar por qué el enchufe está descompuesto.

- Si

la hipótesis fue rechazada, elaboraríamos una nueva. Por ejemplo, la

siguiente hipótesis podría ser que hay un alambre roto en el tostador.

En la mayoría de los casos, el método científico es un proceso

repetitivo.

En otras palabras, es un ciclo más que una línea recta. El resultado de

una ronda se convierte en la información que mejora la siguiente ronda

de elaboración de preguntas.

Los biólogos y otros científicos usan el

método científico para

hacerse preguntas acerca del mundo natural. El método científico

empieza con una observación, la cual lleva a los científicos a hacerse

una pregunta. Entonces él o ella plantearán una

hipótesis, una explicación comprobable que responda a la pregunta.

Una

hipótesis no necesariamente es correcta. Más bien es la "mejor

suposición" y los científicos deben ponerla a prueba para ver si

realmente es correcta. Los científicos comprueban las hipótesis haciendo

predicciones: si la hipótesis \text XX es correcta, entonces \text

YY debería ser cierta. Luego, realizan experimentos u observaciones para

ver si las predicciones son correctas. Si lo son, la hipótesis tiene

sustento. Si no, es el momento de plantear nuevas hipótesis.

¿Cómo se comprueban las hipótesis?

Cuando es posible, los científicos comprueban sus hipótesis usando experimentos controlados. Un

experimento controlado es

una prueba científica hecha bajo condiciones controladas, esto es, que

solo uno (o algunos) factores cambian en un momento dado, mientras que

el resto se mantiene constante. En la siguiente sección estudiaremos a

detalle los experimentos controlados.

En algunos casos, no hay

manera alguna de comprobar una hipótesis por medio de un experimento

controlado (ya sea por razones prácticas o éticas). En ese caso, un

científico puede poner a prueba la hipótesis haciendo predicciones sobre

patrones que deberían verse en la naturaleza si la hipótesis es

correcta. Entonces, puede recopilar datos para ver si el patrón

realmente está allí.

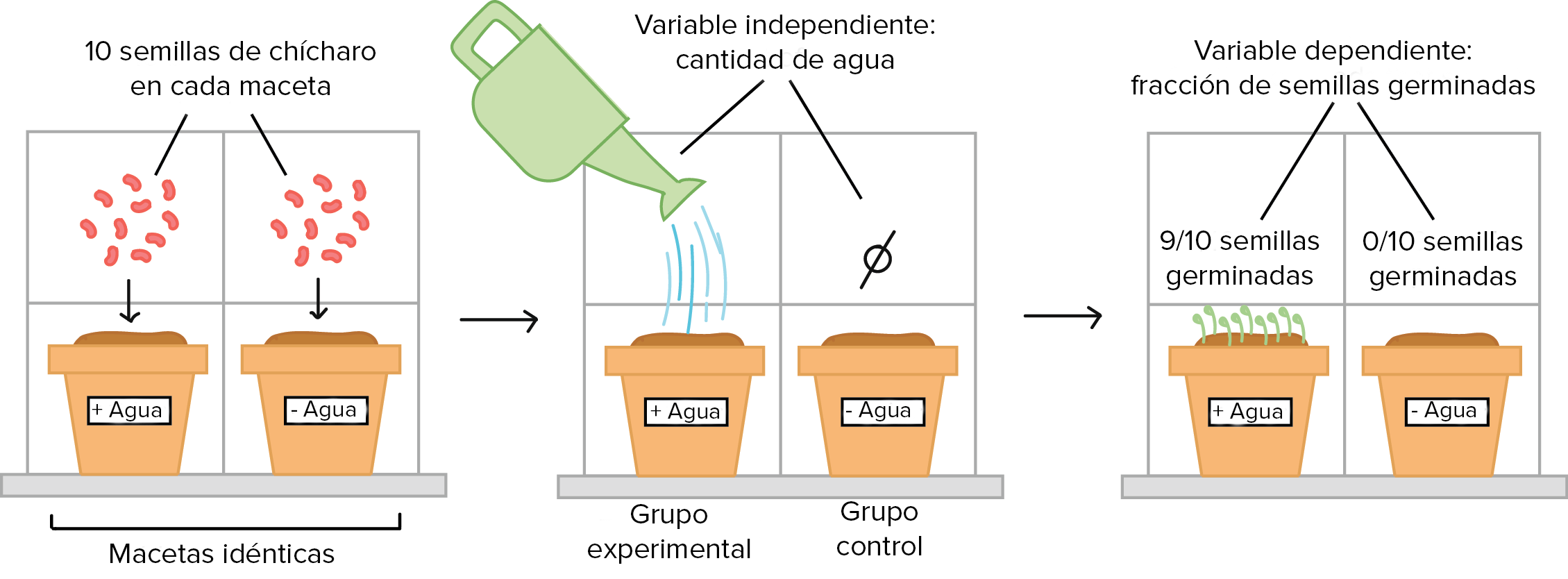

Experimentos controlados

¿Cuáles

son los ingredientes principales de un experimento controlado? Para

ilustrarlo, consideremos un ejemplo sencillo (incluso algo bobo).

Supón

que decido cultivar germen de soya en mi cocina, cerca de la ventana.

Siembro unas semillas de soya en una maceta con tierra, los pongo en el

alféizar de la ventana y espero a que germinen. Sin embargo, después de

varias semanas, no hay germinado. ¿Por qué? Bueno... resulta que olvidé

regar las semillas. Así que mi hipótesis es que no germinaron por falta

de agua.

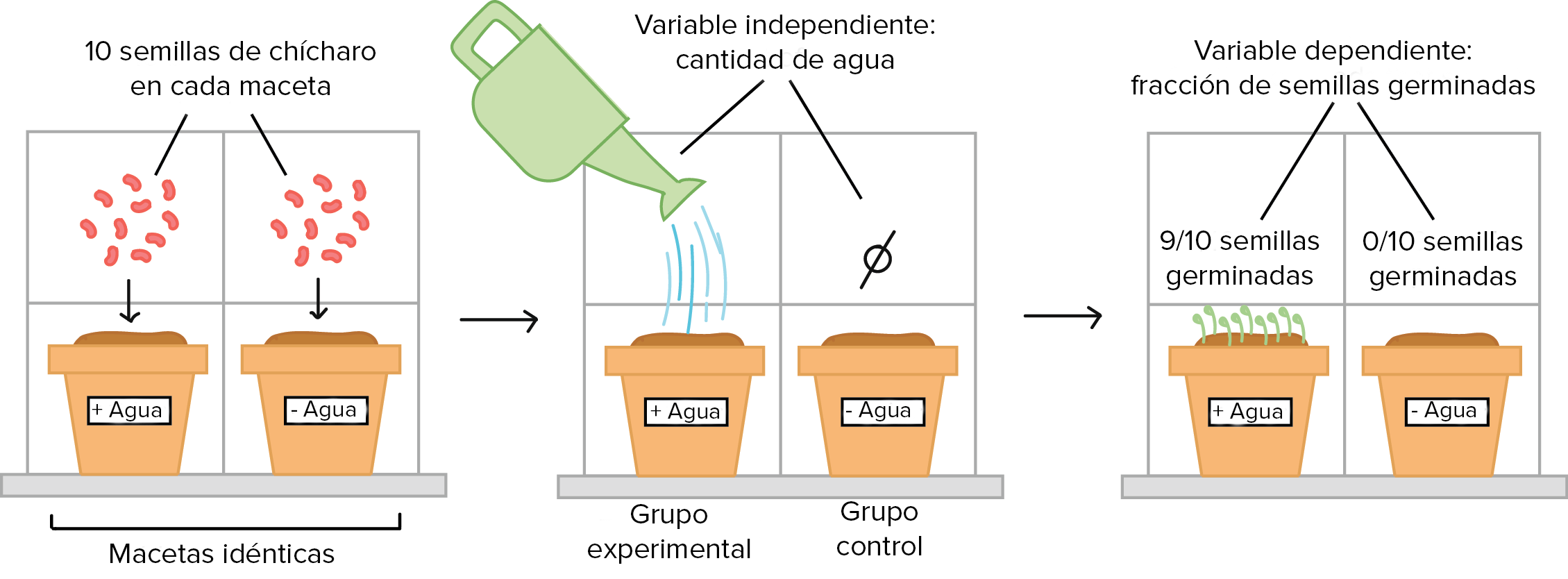

Para comprobar mi hipótesis, realizo un experimento

controlado. Para ello, coloco dos macetas idénticas. Ambas tienen diez

semillas de soya sembradas en el mismo tipo de tierra y están colocadas

en la misma ventana. De hecho, solo hay algo que las diferencia:

- Riego una de las macetas todas las tardes.

- La otra maceta no recibe nada de agua.

Después

de una semana, germinaron nueve de diez semillas de la maceta que

recibe riego, mientras que en la maceta seca no germinó ninguna. ¡Parece

que la hipótesis "las semillas necesitan agua" es probablemente

correcta!

Veamos cómo este sencillo experimento ilustra las partes de un experimento controlado.

Panel 1: se preparan dos macetas idénticas. Se siembran 10 semillas en cada una. Las macetas se colocan cerca de la ventana.

Panel

2: se riega una de las macetas (grupo experimental). La otra maceta no

recibe agua (grupo control). La variable independiente es la cantidad de

agua proporcionada.

Panel 3: en la maceta experimental (con

riego), germinaron 9/10 semillas. En la maceta control (sin riego),

germinaron 0/10. La fracción de semillas germinadas en la variable

dependiente.

Grupos control y experimental

Hay dos

grupos en el experimento, los cuales son idénticos excepto porque uno

recibe un tratamiento (agua) y el otro no. El grupo que recibe el

tratamiento (en este caso, la maceta con agua) se llama

grupo experimental, mientras que el que no lo recibe (en este caso, la maceta seca) se denomina

grupo control. El grupo control proporciona la base que nos permite ver si el tratamiento tiene algún efecto.

Variables dependientes e independientes

El factor que es diferente entre el grupo experimental y el control (en este caso, la cantidad de agua) se conoce como

variable independiente.

Esta variable es independiente porque no depende de lo que pase en el

experimento. De hecho, es algo que el investigador elige, hace o añade

al experimento.

En contraste, la

variable dependiente en

un experimento es la respuesta que medimos para ver si el tratamiento

tuvo algún efecto, que en este caso es la cantidad de semillas

germinadas. La variable dependiente

depende de la variable independiente (en este caso, la cantidad de agua) y no al revés.

Los

datos experimentales son las observaciones hechas durante el experimento. En este caso, los

datos recopilados son la cantidad de semillas de soya germinadas después de una semana.

Variabilidad y repetición

Solo

nueve de las diez semillas de soya que fueron regadas germinaron. ¿Qué

sucedió con la décima? Puede que estuviera muerta, enferma o que solo

fuera lenta para germinar. Con frecuencia existen variaciones en el

material usado para experimentos, especialmente en biología (que estudia

seres vivos complejos), que el investigador no puede ver (en este caso,

la condición de las semillas de soya).

Debido al potencial de

variación que pueden tener, los experimentos en biología necesitan un

tamaño muy grande de muestra y, de manera ideal, repetirse varias veces.

El

tamaño de la muestra se refiere al número de

individuos puestos a prueba en un experimento, en este caso

las 1010 semillas de soya por grupo. Una muestra más grande y varias

repeticiones del experimento hacen que sea menos probable que lleguemos a

una conclusión errónea debido a la variación aleatoria.

Los biólogos y otros científicos también usan

pruebas estadísticas que

les ayudan a distinguir las diferencias reales de las causadas por

variación aleatoria (al comparar, por ejemplo, los grupos experimental y

control).

Experimento controlado de estudio de caso: el blanqueamiento de coral y el \text{CO}_2CO2

Como

un ejemplo más realista de un experimento controlado, analicemos un

estudio reciente sobre blanqueamiento de coral. Normalmente los corales

tienen pequeños organismos fotosintéticos que viven dentro de ellos y el

blanqueamiento sucede cuando dejan el coral, generalmente debido a

estrés ambiental. La fotografía siguiente muestra un coral blanqueado

frente a uno saludable, que se ve en la parte de atrás.

Fotografía que muestra un coral blanqueado en primer plano y un coral sano, color café, al fondo.

Crédito de imagen: "Blanqueamiento de los corales de Keppel" (CC BY 3.0)

Mucha

de la investigación sobre las causas del blanqueamiento se ha

concentrado en la temperatura del agua^11. Sin embargo, un equipo de

investigadores australianos elaboró la hipótesis de que otros factores

podrían ser importantes también. Específicamente, pusieron a prueba la

hipótesis de que los altos niveles de \text{CO}_2CO2, que acidifican el

agua de mar, podrían promover el blanqueamiento también^22.

¿Qué tipo de experimento harías

tú para comprobar esta hipótesis? Piensa en:

- ¿Cuál sería tu grupo experimental y cuál tu control?

- ¿Cuáles serían tus variables dependientes e independientes?

- ¿Cuál sería la predicción de los resultados para cada grupo?

¿Lo intentaste?

\text{pH}

- \text {pH}8.2

- \text{CO}_2\text{pH}7.9\text {pH}7.65

- \text{pH}

- 55

Dispositivo experimental para probar los efectos de la acidez del agua sobre el blanqueamiento del coral.

Grupo control: se colocan fragmentos de coral en un tanque con agua de mar normal (pH 8.2).

Grupo experimental 1: se colocan fragmentos de coral en un tanque con agua de mar ligeramente acidificada (pH 7.9).

Grupo experimental 2: se colocan fragmentos de coral en un tanque con agua de mar más fuertemente acidificada (pH 7.65).

La acidez del agua es la variable independiente.

Se permite que transcurran 8 semanas para cada uno de los tanques.

Grupo control: en promedio hay un blanqueamiento del 10% en los corales.

Grupo experimental 1 (acidez media): en promedio, hay un blanqueamiento de cerca del 20% en los corales.

Grupo experimental 2 (acidez alta): en promedio, hay un blanqueamiento de cerca del 40% en los corales.

El grado de blanqueamiento del coral es la variable dependiente.

\text {pH}\text {pH}7.0

20\%40\%10\%

Prueba de hipótesis no experimental

Algunos

tipos de hipótesis no pueden comprobarse por medio de experimentos

controlados, ya sea por razones éticas o prácticas. Por ejemplo, una

hipótesis acerca de la infección viral no puede ponerse a prueba con

personas sanas y dividiéndolas en dos grupos para infectar a uno de

ellos: infectar a personas sanas no sería ético ni seguro. Del mismo

modo, un ecólogo que estudia los efectos de la lluvia no puede hacer que

llueva en una parte del continente mientras mantiene otra seca como

control.

En situaciones como estas, los biólogos pueden usar

formas no experimentales de comprobación de hipótesis. En una prueba de

hipótesis no experimental, un investigador predice observaciones o

patrones que deberían verse en la naturaleza si la hipótesis es

correcta. Luego recopila y analiza los datos para ver si los patrones

están presentes.

Estudio de caso: la temperatura y el blanqueamiento de coral

Un

buen ejemplo de prueba de hipótesis basada en observación proviene de

los primeros estudios sobre el blanqueamiento del coral. Como se

mencionó anteriormente, el blanqueamiento de coral sucede cuando los

corales pierden los microorganismos fotosintéticos que viven dentro de

ellos, lo que hace que se vuelvan blancos. Los investigadores

sospecharon que la alta temperatura del agua podría ser la causa del

blanqueamiento y pusieron a prueba esta hipótesis de manera experimental

a pequeña escala (utilizando fragmentos aislados de coral cultivados en

tanques)^{3,4}3,4.

Lo que más les interesaba saber a los

ecólogos era si la temperatura del agua estaba causando el

blanqueamiento de muchas especies distintas de coral en su hábitat

natural. Esta pregunta, mucho más amplia, no podía responderse de manera

experimental, ya que no sería ético (ni siquiera posible) cambiar

artificialmente la temperatura del agua alrededor de los arrecifes de

coral.

Mapa

coloreado que representa las temperaturas superficiales del mar

alrededor del mundo con diferentes colores. Los colores más cálidos, la

mayoría cercanos al ecuador, representan temperaturas más calientes,

mientras que los mas fríos, la mayor parte cerca de los polos,

representan temperaturas más frías.

Crédito de imagen: "Temperatura superficial del mar en el mundo", de NASA (dominio público)

En

cambio, para probar la hipótesis de que las ocurrencias de

blanqueamiento naturales eran provocadas por aumentos en la temperatura

del agua, un equipo de investigadores hizo un programa de computadora

para predecir eventos de blanqueamiento basados en información de tiempo

real sobre la temperatura del agua. Por ejemplo, este programa

generalmente podría predecir el blanqueamiento de un arrecife en

particular cuando la temperatura del agua en el área del arrecife

excediera su máxima promedio mensual por 11^\circ \text C∘C o más^{1}1.

El

programa fue capaz de predecir muchos eventos de blanqueamiento semanas

o incluso meses antes de que fueran reportados, incluyendo un evento de

blanqueamiento muy grande en la Gran Barrera de Coral en 1998^{1}1. El

hecho de que un modelo basado en la temperatura pudiera predecir los

eventos de blanqueamiento apoyaba la hipótesis de que las altas

temperaturas del agua provocan el blanqueamiento en los arrecifes de

coral.

https://cerebrodigital.org/post/Que-es-el-metodo-cientifico-y-como-aplicarlo?fbclid=IwAR0Yd01tYHRs3vYfmRBmtGixj4bsm5yAchT55oM2f63kU4zdPseTulOZY6g

Via