Especialista en el Sarcoma de Ewing. Médico patólogo y jefe de servicio de Anatomía Patológica del Virgen del Rocío, Enrique de Álava (Pamplona 1964) es investigador responsable en el Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla (IBIS), especializado en el Sarcoma de Ewing (el que sufría Elena Huelva),

coordinador del Plan de medicina personalizada y de precisión en la

Consejería de Salud y coordinador del programa de Diagnósticos y

Terapias de Precisión en el área de Cáncer del Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red CIBER. Compatibiliza el diagnóstico en este hospital universitario con la investigación, la docencia en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Sevilla y

la gestión hospitalaria. Médico como su padre, procede de una familia

navarra con raíces vascas, valencianas, madrileñas, pero se considera

navarro. Lleva 20 años fuera de su tierra y 10 viviendo en Sevilla.

Casado y con dos hijos de 23 y 19, se organiza bien y le gusta trabajar

en equipo. Se levanta a las 6:00, media hora de meditación para repasar

el día anterior y dar gracias por la vida, y va al trabajo en Sevici.

Le gusta la música, leer, filosofar, la bici, la fotografía y tomar

tapitas. Muy curioso e inquieto, forma parte de la directiva de la

asociación Sevilla Quiere Metro y está ligado con su comunidad cristiana a la acogida de inmigrantes en Casa Mambré.

-Pocas personas saben que la labor de los patólogos es fundamental en un hospital...

-Somos médicos invisibles y, sin embargo, tenemos un

papel fundamental porque ponemos nombres y apellidos a las enfermedades.

El tratamiento que el médico da al paciente depende muchas veces de

nuestro diagnóstico. Somos clave en la toma de decisiones clínicas. De

hecho, no se pone una quimioterapia o una radioterapia sin que lo diga

un patólogo. El cáncer no es una enfermedad, sino cientos de

enfermedades diferentes. Los patólogos estudiamos biopsias (del griego

'mirar la vida') o citologías que nos llegan. Usamos el microscopio y

analizamos los genes para poder poner nombres y apellidos a las

enfermedades.

-¿Podremos acabar algún día con el cáncer gracias al avance de la ciencia?

-Yo pondría otro símil: ¿hemos acabado con el Sida? No,

porque sigue habiendo virus, pero hemos conseguido que se convierta en

una especie de enfermedad crónica, la podemos tratar y muy poca gente se

muere de Sida en el primer mundo. Con el cáncer el problema es que hay

tantos tipos de cáncer que necesitas investigación para cada uno de

ellos. Por eso es infinitamente más complicado, porque cada cáncer tiene

su origen. En algunos cánceres se ha avanzado en el tratamiento y han

mejorado muchísimo. Por ejemplo, el cáncer infantil: hace 60 años era

mortal y ahora la mayor parte evolucionan bien; la excepción son un

pequeño grupo de pacientes con cáncer que no responde, como es el

Sarcoma de Ewing y muchos más, y es ahí donde hay que insistir. Así

pues, el cáncer se cura con prevención, con un buen diagnóstico, con

buen tratamiento y también con investigación. Hay que dar mucho más

dinero a la investigación.

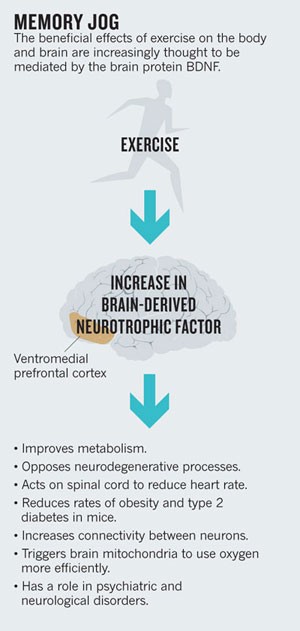

-Hay expertos que vaticinan que acabaremos con el cáncer y las enfermedades neurológicas

-La recuperación de enfermedades neurológicas está

todavía más lejos que la solución al cáncer. Mi sueño es que el cáncer

se convierta en una enfermedad crónica.

La prevención es la clave. Si dejásemos de fumar, la

tercera parte de las muertes por cáncer desaparecerían. El cáncer es una

pandemia. También lo son los altos niveles de grasas en sangre, el

azúcar y los hidratos de carbono. Hay que seguir avanzando en la

investigación, pero también hay que prevenir.

-¿El cáncer se hereda en los genes?

-A la gente le preocupa que el cáncer sea hereditario,

pero hay que decir que solo un 15% del cáncer es hereditario. El resto

de los cánceres tiene que ver con los genes de las células, pero esos

“genes malos” no se heredan. Digamos que las mutaciones tienen lugar en

esas células tumorales en ese momento concreto y esas células cambian y

se hacen malas. Lo que hace que esas células se malignicen son

fundamentalmente los hábitos de vida.

La buena noticia es que buena parte del cáncer es prevenible si nos tomamos en serio las 12 claves que recomienda el Código Europeo contra el Cáncer.

-¿Qué lugar ocupa Andalucía en la investigación sobre cáncer?

-En investigación biomédica, a lo que me dedico,

Andalucía ha dado pasos importantes. Tiene buenos institutos de

investigación cerca de los hospitales, como el IBIS de Sevilla,

el segundo instituto que se creó en España; un centro de investigación

puntero donde se investiga sobre cáncer y muchas otras cuestiones, y muy

bien integrado con los hospitales Virgen del Rocío y Macarena. Hay

otros excelentes centros de investigación no ligados a hospitales como

el CABIMER en Sevilla y el GENYO

en Granada. En suma, en Andalucía hay buenos institutos de

investigación y se hace investigación en los hospitales. Además, la

Consejería de Salud siempre ha tenido programas para fomentar la

investigación en los centros sanitarios.

Quizás lo más destacable en Andalucía es que va a crear la figura de los clínicos investigadores con plaza en propiedad,

que pueden realizar diagnóstico e investigación, y eso ha sido un logro

de esta Consejería. Tener un contrato fijo de funcionario que te

permita hacer investigación y asistencia prácticamente no existe en

España.

-Aparte de la medicina, está implicado en el impulso ciudadano del Metro desde la asociación Sevilla Quiere Metro

-Quiero dejar el mundo mejor de como me lo he encontrado y

aportar cambios, siempre de manera constructiva. Formar parte de la

directiva de la asociación Sevilla Quiere Metro es de las mejores

decisiones en estos dos años. Es necesario un transporte eficiente como

el Metro, que vertebra socialmente los barrios de Sevilla y permite que

la gente pueda elegir dónde vivir. El Metro también puede mejorar la

calidad del aire: 400.000 personas mueren al año en Europa por

enfermedades asociadas a la mala calidad del aire por el uso de

combustibles fósiles. El tráfico motorizado es uno de los causantes.

-Sevilla necesita con urgencia completar su red de Metro

-Todas las administraciones están haciendo su trabajo,

pero hay que pedirles que aceleren los trámites porque llevamos un

retraso de 30 años. ¿De qué hablamos? Del tramo Sur de la línea 3, cuyo

proyecto está en fase final de revisión y hay que ponerlo en información

pública para que la gente lo conozca. El proyecto de la línea 2 quedó desfasado y hay que actualizarlo en 2023

para captar fondos europeos y empezar las obras en 2028. Hay dinero en

los presupuestos de Andalucía de este año para actualizarlo.

-Su preocupación por la pobreza y la inmigración le llevó a abrir Casa Mambré en Sevilla

-Decidimos abrir con mi comunidad cristiana Casa Mambré,

un grupo de hospitalidad que acoge inmigrantes, sobre todo

subsaharianos. Caritas colabora con nosotros recomendándonos los

perfiles que podemos acoger. En los últimos siete años, 40 personas que

han pasado por Casa Mambré han logrado inserción laboral tras completar

sus estudios de la ESO o FP. Tenemos cuenta en twitter, facebook e

instagram y admitimos donaciones para apoyar el proyecto.