Los ingenieros de la Universidad de Massachusetts Amherst han creado la primera neurona artificial que imita genuinamente el comportamiento eléctrico de una célula cerebral real e incluso puede comunicarse con neuronas biológicas

UMass Engineers Create First Artificial Neurons That Could Directly Communicate With Living CellsUMass Engineers Create First Artificial Neurons That Could Directly Communicate With Living Cells : Riccio College of Engineering : UMass Amherst

Este avance, publicado en Nature Communications en octubre de 2025, representa un hito en la computación neuromórfica y la bioelectrónica. Aquí te explico los aspectos más destacados:

¿Qué hace única a esta neurona artificial?

Imita el voltaje de las neuronas reales: A diferencia de versiones anteriores que requerían voltajes mucho más altos, esta neurona artificial opera con apenas 0.1 voltios, igual que las neuronas humanas

Puede comunicarse con células vivas: Gracias a su bajo voltaje y diseño biocompatible, puede integrarse directamente con neuronas biológicas sin necesidad de amplificación eléctrica.

Consumo energético ultraeficiente: Genera impulsos eléctricos con apenas unos picojulios por evento, comparable al rango de 0.3 a 100 picojulios de las neuronas reales

Imita el voltaje de las neuronas reales: A diferencia de versiones anteriores que requerían voltajes mucho más altos, esta neurona artificial opera con apenas 0.1 voltios, igual que las neuronas humanas

Puede comunicarse con células vivas: Gracias a su bajo voltaje y diseño biocompatible, puede integrarse directamente con neuronas biológicas sin necesidad de amplificación eléctrica.

Consumo energético ultraeficiente: Genera impulsos eléctricos con apenas unos picojulios por evento, comparable al rango de 0.3 a 100 picojulios de las neuronas reales

Cómo lo lograron?

Uso de nanocables de proteínas: El equipo empleó memristores construidos con nanocables derivados de la bacteria Geobacter sulfurreducens, conocida por su capacidad de generar electricidad.

Circuito RC simple: Al conectar estos memristores a un circuito básico, lograron emular el proceso de carga y descarga típico de las neuronas, generando picos de voltaje repetibles que activan otras neuronas artificiales, igual que en el cerebro humano

Aplicaciones futuras

Computadoras bioinspiradas: Este tipo de neuronas podría revolucionar el diseño de sistemas informáticos, haciéndolos más eficientes y capaces de aprender como el cerebro humano.

Dispositivos biomédicos avanzados: Sensores que interactúan directamente con el cuerpo sin amplificación, prótesis inteligentes, o interfaces cerebro-máquina más naturales.

Computadoras bioinspiradas: Este tipo de neuronas podría revolucionar el diseño de sistemas informáticos, haciéndolos más eficientes y capaces de aprender como el cerebro humano.

Dispositivos biomédicos avanzados: Sensores que interactúan directamente con el cuerpo sin amplificación, prótesis inteligentes, o interfaces cerebro-máquina más naturales.

Este desarrollo no solo acerca la tecnología al funcionamiento del cerebro, sino que también abre la puerta a una nueva era de dispositivos que combinan lo biológico con lo electrónico

Interfaces cerebro-máquina más naturales

Estas neuronas podrían integrarse directamente con el sistema nervioso, permitiendo prótesis que se controlan con el pensamiento o dispositivos que restauran funciones perdidas, como la visión o el movimiento.

Tratamientos personalizados para enfermedades neurológicas

Al replicar el comportamiento de neuronas reales, podrían usarse para estudiar enfermedades como el Alzheimer, Parkinson o epilepsia en entornos controlados, facilitando el desarrollo de terapias más precisas.

Sensores biomédicos ultraeficientes

Dispositivos implantables que monitorean señales neuronales en tiempo real sin necesidad de baterías grandes ni amplificadores, gracias a su bajo consumo energético.

Dispositivos implantables que monitorean señales neuronales en tiempo real sin necesidad de baterías grandes ni amplificadores, gracias a su bajo consumo energético.

Aplicaciones en inteligencia artificial

Computación neuromórfica

Sistemas informáticos que imitan el cerebro humano, capaces de aprender, adaptarse y procesar información de forma más eficiente que los algoritmos tradicionales.

Robots con percepción más humana

Robots que procesan estímulos como el tacto, el sonido o la visión de forma similar al cerebro, mejorando su capacidad de interacción con humanos y entornos complejos

Computación neuromórfica

Sistemas informáticos que imitan el cerebro humano, capaces de aprender, adaptarse y procesar información de forma más eficiente que los algoritmos tradicionales.

Robots con percepción más humana

Robots que procesan estímulos como el tacto, el sonido o la visión de forma similar al cerebro, mejorando su capacidad de interacción con humanos y entornos complejos

Redes neuronales híbridas

Combinación de neuronas artificiales y biológicas para crear sistemas de IA que aprenden de forma orgánica, con aplicaciones en educación, arte, y toma de decisiones complejas.

Este tipo de tecnología nos acerca a una frontera donde lo biológico y lo digital se fusionan

Redes neuronales híbridas

Combinación de neuronas artificiales y biológicas para crear sistemas de IA que aprenden de forma orgánica, con aplicaciones en educación, arte, y toma de decisiones complejas.

Constructing artificial neurons with functional parameters comprehensively matching biological values

Nature Communications 16, Article number: 8599 (2025)

Abstract

The efficient signal processing in biosystems is largely attributed to the powerful constituent unit of a neuron, which encodes and decodes spatiotemporal information using spiking action potentials of ultralow amplitude and energy. Constructing devices that can emulate neuronal functions is thus considered a promising step toward advancing neuromorphic electronics and enhancing signal flow in bioelectronic interfaces. However, existent artificial neurons often have functional parameters that are distinctly mismatched with their biological counterparts, including signal amplitude and energy levels that are typically an order of magnitude larger. Here, we demonstrate artificial neurons that not only closely emulate biological neurons in functions but also match their parameters in key aspects such as signal amplitude, spiking energy, temporal features, and frequency response. Moreover, these artificial neurons can be modulated by extracellular chemical species in a manner consistent with neuromodulation in biological neurons. We further show that an artificial neuron can connect to a biological cell to process cellular signals in real-time and interpret cell states. These results advance the potential for constructing bio-emulated electronics to improve bioelectronic interface and neuromorphic integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The boundary between electronics and biosystems is an increasingly important research area1. On one hand, biosystems provide enormous inspiration for advancing electronics through functional emulations2,3,4; on the other hand, bio-emulated electronics are often used to interface with biosystems to gain further biological understanding or improve biological functions5,6,7. These two directions often benefit each other mutually. A notable example is the development of memristors and associated neuromorphic electronics. The analog conductance modulation in nonvolatile memristors was initially used to emulate synaptic plasticity8, which was later incorporated into neural computing networks9,10,11. Similarly, the spontaneous conductance relaxation in some volatile memristors has been employed for constructing basic integrate-and-fire neuronal functions12,13, with potential applications for spiking neural networks. Concurrently, the bio-emulated functions of these neuromorphic devices make them promising candidates for improving signal translation in bioelectronic interfaces14,15,16,17,18,19.

Developing artificial neurons with improved functionalities is of particular interest because neurons inherently possess rich computing capabilities12,13. Expanding the functionality of artificial neurons to more closely match their biological counterparts can lead to more efficient signal processing with reduced circuitry and energy consumption13,14, which is especially beneficial for bioelectronic interfaces. To achieve this, artificial neurons have been constructed using various devices to emulate basic neuronal functions, such as spiking generation and signal integration12,13,14,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The integration functions are further utilized to process bioelectronic signals from environmental, bodily, and physiological stimuli for bio-realistic interpretation14,15,16,17,18,31,32,33,34,35.

Despite advancements in functional emulation, a significant gap remains between artificial neurons and their biological counterparts. Specifically, biological neurons use ultralow signal amplitudes (e.g., action potentials of 70–130 mV)36, whereas demonstrated artificial neurons work with amplitudes ≥0.5 V12,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The ultralow amplitudes facilitate seamless signal flow between sensory and computing functions in biosystems, enabling exceptional processing efficiency. Therefore, achieving parameter matching is crucial for enhancing efficiency in bio-emulated/integrated systems, including improving signal translation in bioelectronic interfaces. Recently, memristors with ultralow operating voltages were used to create artificial neuronal components, demonstrating that bio-amplitude signals (e.g., <130 mV) could induce state changes16,25,32,37. The state change was further manifested by threshold event of a current spike mimicking neuronal firing32. However, the discontinued (one-time) current spike still differs from repeated voltage spikes seen in actual neuronal firing, limiting the potential for signal cascading and realistic bioelectronic interactions.

We demonstrate artificial neurons capable of integrating bio-amplitude signals and producing continuous voltage spikes that resemble action potentials. The artificial neurons are built from a type of memristor uniquely designed to operate with ultralow voltage and current signals. The construct incorporates components that can fundamentally emulate key dynamic processes involved in neuronal firing. As a result, these artificial neurons achieve not only close functional emulation but also parameter matching in crucial aspects such as signal amplitude, spiking energy, temporal features, frequency response, and dynamics tuning. Moreover, these artificial neurons can be integrated with chemical sensors to emulate neuromodulation by extracellular substances (e.g., ions and neurotransmitters) in a manner consistent with biological neurons. Furthermore, we demonstrate that an artificial neuron can connect to a biological cell to process cellular signals in real time and interpret cell states. These advancements enhance the potential for constructing bio-emulated electronics to improve bioelectronic interface and neuromorphic integration.

Results

The constituent bio-amplitude memristor

A biological neuron can be stimulated by injected excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) to raise its intracellular charge (Q), thus the membrane potential (Fig. 1a, top panel). The charge accumulation () is the competing result of EPSC injection (I) and membrane current leakage (I’), or . Upon a certain threshold, it triggers the broad opening of sodium channels for Na+ influx to quickly raise the membrane potential, forming the fast depolarization in an action potential36. Coincidently, the atomic accumulation () of the filament in a memristor can be similarly viewed as the competing result of the ionic current injection (IM+) and leaky current (I’M+) diffusing outward the filamentary volume (Fig. 1a, bottom panel), or . As a result, the atomic integration process in a memristor can mimic the charge integration in a neuron25. The eventual filament bridging is like triggered depolarization. At the peak of depolarization, the sodium channels are self-deactivated for entering into the repolarization phase36. Although self-deactivation is absent in a memristor, the instability of filament in some volatile memristors can be utilized for facilitation21. These inherent dynamics of filamentary volatile memristors make them promising candidates for emulating the integration function of biological neurons12,13.

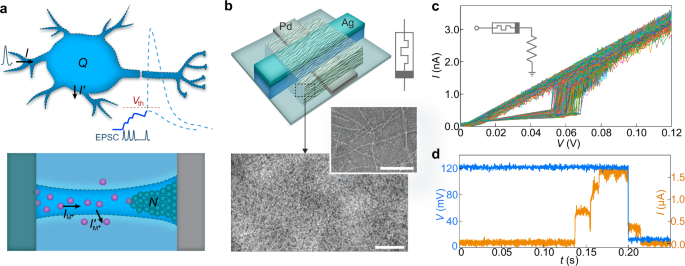

a (Top) Schematic of an integrate-and-fire neuron model involving EPSC injection (I) and membrane current leakage (I’). The blue curve illustrates the evolution of membrane potential by charge integration from competing I and I’. Depending on whether the integration reaches the threshold (Vth) or not, it can either elicit an action potential or fade away (dashed lines). (Bottom) Schematic of the dynamics of a metal filament formation in a memristor. The dashed lines delineate the filamentary volume. The purple dots indicate metal ions (M+). b (Top) Schematic of the memristor structure involving protein nanowires. (Bottom) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of protein nanowires in a sparse (upper) and dense (lower) network. Scale bars, 100 nm. c 1000 I-V sweeps from a fabricated memristor connected with a resistor (inset). d Current (orange) response in a memristor applied with a voltage pulse (blue). The amplitude of the pulse switched from 120 mV to 10 mV (as reading voltage) at t = 0.2 s.

However, biological neurons achieve the integrate-and-fire function with very low amplitudes in key parameters, including ultralow action potential amplitudes (e.g., <130 mV) that serve as the fundamental processing signal. The efficient charge selectivity across the cell membrane also ensures that an injected current as low as several nanoamperes (nA) can generate sufficient potential to elicit an action potential36. These parameters result in ultralow spiking energy (e.g., 0.3–100 pJ)38,39,40, which ensures biocomputational efficiency and maintains a safe, non-reactive electrochemical environment. To achieve parameter matching in an artificial neuron, one conceivable approach is to use a memristor with functional parameters (e.g., voltage, current) that fall within biological ranges. Nevertheless, most filamentary memristors operate at voltages >0.5 V. Among the few that achieved bio-amplitude voltages, the reported working currents were typically >1 µA14,41.

We previously demonstrated that thin films assembled from protein nanowires harvested from the microbe Geobacter sulfurreducens can be used in device applications due to their excellent stability25,42,43,44, which is attributed to their design as extracellular structures in natural environments. Their molecular size (e.g., 2–3 nm diameter) ensures that the assembled thin film has a dense structure similar to that of a conventional dielectric (Fig. 1b, bottom). Specifically, they are designed to facilitate the microbe’s charge exchange involved in redox processes42. Introducing the protein nanowires into an Ag-based memristor significantly reduced the functional voltage to bio-amplitude regime25, although the switching performance under ultralow current has not yet been studied. Therefore, we constructed memristors with a similar device structure (top, Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 1) to study switching behavior with current injections at biological levels (e.g., 2 nA). To restrict the current, a series resistor (28 MΩ) was connected to the memristor. A continuous series of 1000 voltage sweeps (0→120 mV→0) were applied to the device (Fig. 1c). The recorded I-V curves reveal several key features desirable for constructing artificial neurons. First, the memristor consistently switched to On states at voltages of ~60 mV and current levels of ~1.7 nA. Both values fall within biological ranges36, supporting the feasibility of constructing artificial neurons with parameters that match biological ones. The Off states maintained a resistance ~200 MΩ, close to the high membrane resistance in cells (e.g., 50–300 MΩ)45. Second, the I-V curves consistently started with an Off state during the consecutive sweeps, showing characteristic volatile switching. The volatility can facilitate the emulation of sodium-channel closure during repolarization. Third, the continuous sweeps yielded narrow distributions of switching voltages (e.g., 60 ± 3 mV S.D.) and currents (e.g., 1.76 ± 0.06 nA S.D.), demonstrating a stability not achieved in other bio-amplitude memristors14. Statistics across different devices showed consistent narrow distributions of these parameters (Supplementary Fig. 2). The switching stability is also crucial for constructing artificial neurons with consistent firing characteristics.

We further examined the switching dynamics of the memristor using pulsed signals (Fig. 1d). Note that the current compliance was lifted due to reduced current resolution in pulsed measurements. When a 120-mV input was applied, the memristor exhibited an integration period before transitioning to the On state (t ~ 0.13 s). As discussed before, this integration period reflects the atomic accumulation in the forming filament, which can emulate the charge integration process in a neuron (Fig. 1a). After the pulse ended (t ~ 0.2 s; followed by a 10-mV reading pulse), the memristor exhibited a delay before transitioning to the Off state (t ~ 0.21 s), indicating a spontaneous filament rupture. This filament rupture requires the cessation of external input, which does not fully replicate the self-regulated closure of the sodium channels during repolarization36. Consequently, previously constructed artificial neurons by directly employing the switching dynamics could not relax to a rest state for continuous firing21,25,32.

Bio-amplitude artificial neuron

To fully utilize the memristor’s multiple bio-amplitude functional parameters and overcome previous limitations, we constructed an artificial neuron by integrating the memristor with an RC circuit (Fig. 2a). Voltage pulses (120 mV, 5 ms) at physiologically relevant frequencies (10–100 Hz)46 were used as emulated action potential input. Unlike previous artificial neurons that could only produce a current output21,25,32, our design employs the voltage across the capacitor as output (Vo), enabling a voltage-to-voltage signal translation similar to that in biological neurons

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario