Los avances médicos han hecho retroceder en las últimas décadas a muchos asesinos implacables, como el cáncer y las cardiopatías. Una amplia gama de tratamientos comparten el mérito: cirugía, medicamentos, radiación, terapias genéticas y hábitos saludables. Las tasas de mortalidad por estas dos enfermedades, las principales causas de muerte en Estados Unidos, han descendido drásticamente. Pero en una población que envejece, las tasas de mortalidad por Alzheimer han ido en dirección contraria.

La arrogancia y la lasitud ante la mala conducta -compartidas por otros financiadores y reguladores, revistas y universidades- tienen que cambiar. La investigación sobre el Alzheimer debe empezar a autocontrolarse eficazmente. Eso significa que las revistas y los financiadores deben invertir más en herramientas informáticas y especialistas para detectar imágenes manipuladas en artículos y subvenciones antes de que contaminen la literatura científica. Y será necesario trasladar las revisiones de las acusaciones graves de fraude a expertos ajenos a la institución de origen del investigador acusado.

Si las autoridades institucionales del sector no actúan, seguramente lo harán los escépticos de la propia ciencia, entre los que probablemente se encuentren los miembros de la administración Trump. Casi con toda seguridad, un ensañamiento subsiguiente describiría la ambigüedad o el error humano inocente como fraude y eludiría el respeto reflexivo y el debido proceso necesarios para preservar lo que sigue siendo vital y verdadero en la neurociencia. Eso impondría una nueva calamidad a todos los que planean envejecer.

Medical advances have beaten back many relentless assassins in recent

decades, such as cancer and heart disease. A wide range of treatments

share credit: surgery, medicines, radiation, genetic therapies and

healthful habits. Mortality rates for those two diseases, the top causes

of death in the United States, have fallen sharply. But in an aging

population, Alzheimer’s death rates have gone in the opposite direction.

The disease afflicts nearly seven million Americans, about one in

every nine people over the age of 65, making it a leading cause of death

among older adults. Up to 420,000 adults in the prime of life —

including people as young as 30 — suffer from early-onset Alzheimer’s.

The annual number of new cases of dementia is expected to double by

2050.

Yet despite decades of research, no treatment has been created that

arrests Alzheimer’s cognitive deterioration, let alone reverses it. That

dismal lack of progress is partly because of the infinite complexity of

the human brain, which has posed insurmountable challenges so far.

Scientists, funders and drug companies have struggled to justify

billions in costs and careers pursuing dead-end paths. But there’s

another, sinister, factor at play.

Over the past 25 years, Alzheimer’s research has suffered a litany of

ostensible fraud and other misconduct by world-famous researchers and

obscure scientists alike, all trying to ascend in a brutally competitive

field. During years of investigative reporting, I’ve uncovered many

such cases, including several detailed for the first time in my forthcoming book.

Take for example the revered neuroscientist Eliezer Masliah, whose

groundbreaking research has shaped the development of treatments for

memory loss and Parkinson’s disease, and who in 2016 was entrusted to

lead the National Institute on Aging’s expanded effort to tackle

Alzheimer’s. With roughly 800 papers to his name, many of them

considered highly influential, Dr. Masliah seemed a natural choice to

steer the project, with billions in new funding. He hailed the moment as

the dawning of “the golden era of Alzheimer’s disease research”.

Last September in Science magazine, I described evidence

that for decades Dr. Masliah’s research had included improperly

manipulated photos of brain tissue and other technical images — a clear

sign of fraud. Many of his studies contained apparently falsified

western blots — scientific images that show the presence of proteins in a

blood or tissue sample. Some of the same images seem to have been used

repeatedly, falsely represented as original, in different papers

throughout the years. (When I reached out to Dr. Masliah for the story,

he declined to respond.)

It’s true that some image abnormalities can be errors introduced by

the publication process. Others might contain innocuous visual artifacts

or human errors that sometimes appear to be image doctoring. But in

some cases, the volume and nature of the evidence (and the failure of

authors to provide raw, original data and images to clear up any

confusion) have convinced outside experts that something more troubling

has occurred. On the day my story was published, the National Institutes

of Health announced that it had found

that Dr. Masliah engaged in research misconduct and that he no longer

held his leadership position at the National Institute on Aging.

Dr. Masliah epitomized a deeper malaise within the field — a crisis

that goes far beyond him. Many Alzheimer’s researchers, including some

once considered luminaries, have recently faced credible allegations of

fraud or misconduct. These deceptions have warped the trajectory of

Alzheimer’s research and drug development, prompting critical concerns

about how bad actors, groupthink and perverse research incentives have

undermined the pursuit of treatments and cures. It haunts me that this

may have jeopardized the well-being of patients.

In my reporting, I asked a team of brain and scientific imaging

experts to help me analyze suspicious studies by 46 leading Alzheimer’s

researchers. Our project did not attempt a comprehensive look at all 46,

let alone the multitude of other Alzheimer’s specialists who

contributed to those projects. That would take an army of sleuths and

years of work. But our effort was, to my knowledge, the first attempt to

systematically assess the extent of image doctoring across a broad

range of key scientists researching any disease.

Collectively, the experts identified nearly 600 dubious papers from

the group that have distorted the field — papers having been cited some

80,000 times in the scientific literature. Many of the most respected

Alzheimer’s scholars — whose work steers the scientific discourse —

repeatedly referred to those tainted studies to support their own ideas.

This has compromised the field’s established base of knowledge.

In some cases, the data problems might have an innocent explanation.

Some researchers who put their names on papers may not have been aware

of errors made by co-authors, but other cases most likely involve

serious negligence, misconduct and outright fraud.

Such wrongdoing in any health-related research is lamentable. But

fraud in the pursuit of treatments for Alzheimer’s is especially tragic

because it’s a disease apart, different in kind from other major killers

of the aging. It generally begins by gradually degrading a person’s

command of routine activities, then stealing cherished memories and

finally the very identity that makes each of us human.

Alzheimer’s families face incalculable emotional costs. In the United

States, more than 11 million family members and other unpaid caregivers

(such as friends and neighbors) care for fathers and mothers, spouses

and grandparents who have fallen prey to dementia. For many this means

financial impoverishment. These caregivers in the United States provided

the equivalent of nearly $350 billion in care to dementia patients in

2023 — nearly matching the amount paid for dementia care by all other

sources, including Medicare. The world desperately needs a cure, which

makes any misconduct all the more insidious. And it raises an urgent

question: Why would a scientist do it?

***

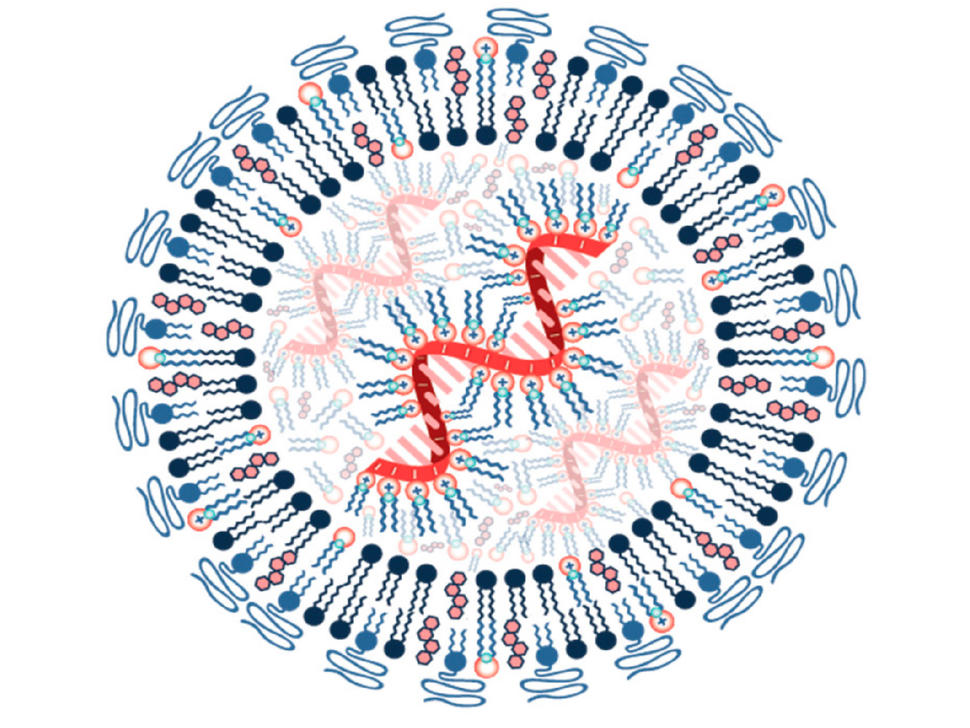

For decades, Alzheimer’s research has been shaped by the dominance of

a single theory, the amyloid hypothesis. It holds that amyloid proteins

prompt a cascade of biochemical changes in the brain that cause

dementia. The supremacy of that hypothesis has exerted enormous pressure

toward scientific conformity.

Even many of the most hardened skeptics of the hypothesis believe

that amyloids have some association with the disease. But since the

early 2000s, doctors, patients and their loved ones have endured decades

of therapeutic failures stemming from it, despite billions of dollars

spent in grants and investments. Its contradictions — such as the

presence of massive amyloid deposits found in the brains of deceased

people who had no symptoms of Alzheimer’s — have long exasperated

critics and prompted doubts among many supporters.

Still, the hypothesis retains enormous influence. Nearly every drug

approved for Alzheimer’s dementia symptoms is based on it, despite

producing meager results. The anti-amyloid antibody drugs approved in

the United States cost tens of thousands of dollars per patient per

year, yet they slow cognitive decline so minutely that many doctors call

the benefits imperceptible. The drugs are also not benign, posing risks

of death or serious brain injury, and they can shrink the brain faster

than Alzheimer’s itself.

The entrenchment of the amyloid hypothesis has fostered a kind of

groupthink where grants, corporate riches, career advancement and

professional reputations often depend on a central idea largely accepted

by institutional authorities on faith. It’s unsurprising, then, that

most of the fraudulent or questionable papers uncovered during my

reporting have involved aspects of the amyloid hypothesis. It’s easier

to publish dubious science that aligns with conventional wisdom.

I learned about Dr. Masliah’s apparent deception while reviewing

suspicious research papers flagged on PubPeer, a website where scholars

and sleuths challenge scientific papers.

A few posts about his work caught my eye. I asked the neuroscientist

Matthew Schrag of Vanderbilt University, the neurobiologist Mu Yang of

Columbia University, the independent forensic-image analyst Kevin

Patrick and the microbiologist and research-integrity expert Elisabeth

Bik to examine his work closely. (Dr. Schrag and Dr. Yang worked

independently from their university jobs.)

Over several months the group created a 300-page dossier comprising

132 papers by Dr. Masliah that they deemed suspicious. (Although the

papers were written with colleagues, Dr. Masliah was the sole common

author and usually played a leading role.) The experiments in those

papers had been cited more than 18,000 times in academic and medical

journals. The scale of apparent misconduct, including in many papers

related to the amyloid hypothesis, uncovered in just a fraction of Dr.

Masliah’s work stunned leading experts.

Although an extreme example, Dr. Masliah fits a pattern of researchers whose work has been called into question.

There’s Berislav Zlokovic, a renowned Alzheimer’s expert at the

University of Southern California, whose research informed the basis of a

major federally funded stroke trial. My 2023 investigation for Science,

aided by the same image sleuths, revealed decades of apparent image

manipulation in his studies. The N.I.H. quickly suspended the stroke

trial. An attorney representing Dr. Zlokovic claimed that some of the

concerns raised about his studies were “based on information or premises

Professor Zlokovic knows to be completely incorrect” or were related to

experiments not conducted in his lab.

Marc Tessier-Lavigne, the former president of Stanford University,

was known as a global leader in research on the brain’s circuitry in

Alzheimer’s and other neurological conditions. He resigned in 2023 after

an intrepid student journalist revealed

numerous altered images in his research. Dr. Tessier-Lavigne didn’t

personally falsify data or coerce junior colleagues to do so. But he

failed to correct dubious results that came to his attention and may

have provided inadequate oversight of his lab — allowing apparently

doctored studies that helped build his reputation to remain on the

scientific record, according to an investigation by a special committee appointed by the university’s board of trustees. In his resignation letter,

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne denied that he had engaged in any unethical

research but admitted that there were instances in which he “should have

been more diligent in seeking corrections”.

Questionable and potentially fraudulent studies by Dr. Masliah and

that of many others, have helped lay the foundation for hundreds of

patents related to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s treatments and

techniques, now being pursued by leading pharmaceutical companies.

For example, Hoau-Yan Wang, whose work contributed to the development

of simufilam — an Alzheimer’s drug tested on thousands of patients —

has faced credible allegations

of image doctoring and manipulated test results. Dr. Wang was indicted

by the Department of Justice in June 2024 on charges that he defrauded

the National Institutes of Health of $16 million in grants. He has

pleaded not guilty. The biopharmaceutical company backing the drug,

Cassava Sciences, settled with the U.S. Securities and Exchange

Commission on charges that the company and key executives had misled

investors on research around the drug. The executives did not admit

wrongdoing.

When extensive and credible doubts cast a pall over a scientific

portfolio, it’s natural to question the integrity of the researcher’s

entire body of work. But not all the research I examined from those

scholars was touched by apparent misconduct; some of them have even made

contributions that could advance neuroscience, which makes this all the

more complicated.

Most Alzheimer’s scholars operate with determination and integrity,

and there are many independent-minded scientists advancing our

understanding of the brain and memory loss. Recently, alternatives to

the amyloid hypothesis have begun to find support.

Promising approaches include exploring the role of viruses in cognitive

decline, treating brain infections and reducing brain inflammation —

potentially with GLP-1 drugs that have transformed weight loss. There’s

also growing evidence that healthy lifestyle choices, as well as

controlling blood pressure and cholesterol, can slow the disease’s

progression.

But widespread misconduct wastes time, steals precious resources and

skews thinking by honest scientists. Meanwhile, the staggering scale of

Alzheimer’s grows year by year.

***

The question of why any scientist would resort to cheating looms

large. Alzheimer’s disease remains one of the most formidable challenges

in medicine, and the persistent lack of progress can feel like a deeply

personal failure. Such frustration seemingly can, at times, drive

normally ethical people to publish provocative results based on doctored

data. The lure of prestige, fame and potential fortune from developing

desperately needed drugs — even those with little or no realistic hope

of benefit — has apparently led astray many who entered the field as

seekers of truth. After all, top Cassava Sciences executives made

millions in salary and stock trades despite simufilam crashing and

burning, as had been long predicted by many experts.

“As a field, we’ve had a lot of dead ends” that have left patients

waiting endlessly for treatments, said Donna Wilcock, an Indiana

University neuroscientist who edits the journal Alzheimer’s &

Dementia. “Some people have put their ego and fame ahead of performing

rigorous science”.

That phenomenon is not isolated to Alzheimer’s research. The broader

incentive structures in science — where pressure to publish, secure

funding and achieve breakthroughs is immense — can lead even

well-meaning scientists to make shocking choices.

A slippery slope sometimes begins when a researcher alters highly

enlarged pictures of brain slices to enhance them aesthetically —

seemingly “harmless” doctoring to clarify biology’s inherent messiness

and ambiguity. Beautiful images increase a paper’s curb appeal for

publishers. (That temptation has been especially enticing amid a

publish-or-perish imperative for scientists that’s so extreme it has

spawned an industry of pay-to-play paper mills. Shady companies churn

out phony scholarly papers, then sell author slots to desperate or

ethically challenged academics.)

Scientists may then find themselves changing an image to strengthen

its frail support for an experimental premise. They might rationalize

their behavior as simply polishing a potentially important outcome.

Scholarly journals have overlooked or been fooled by such deceits over

and over. Scientists who are devoted to their assumptions regardless of

the evidence — or outright cynics — may then take that deceit a step

further. They fundamentally change images to fit their hypotheses:

unambiguous misconduct.

Decades of complacency by funders, journals and academic institutions

that manage the research enterprise means that relatively few cases of

such fraud have been caught. For example, few peer reviewers who certify

a paper’s scientific quality have the skill to check for image

tampering. Despite years of scandals, many journal editors don’t verify

images either. And few perpetrators face meaningful consequences.

So with professional rewards potentially great, many scientists,

including those of high standing, seem to roll the dice. They surely

know that misconduct investigations are nearly always conducted by an

accused researcher’s home university, which fears the loss of face and

funding that might follow a prompt, robust and open process. Such

investigations — often lasting many months or years — usually start and

finish behind a bureaucratic veil, hidden from public view.

Dr. Schrag of Vanderbilt, one of the neuroscientists I’ve worked with

to uncover cases of scientific fraud, told me he used to view

misconduct in Alzheimer’s research as rare, but has since gone through a

“stages-of-grief process”.

“It doesn’t take that high a percentage of fraud in this discipline

to cause major problems, especially if it’s strategically placed”, he

added. “Patients ask me why we’re not making more progress. I keep

telling them that it’s a complicated disease. But misconduct is also

part of the problem”.

Exposing misconduct is the first essential, painful step for course

correction, both to clean up the scientific record and to alert people

to how compromised the field has become. Fixing a broken system — and

accelerating the hunt for effective Alzheimer’s treatments — will also

require new thinking about academic incentives and culture. One place to

start: Train young researchers to value ethical conduct as the

fundamental basis of science, and to hone their powers of skepticism.

Advance them based on the quality rather than the quantity of their

research products.

Government agencies that oversee Alzheimer’s research and enormously

influence the field also need to rethink how they operate, and to move

with urgency. Officials of the National Institutes of Health, of which

the National Institute on Aging is a part, didn’t inspire confidence in

response to the questions I sent them about Dr. Masliah as I conducted

my 2024 investigation for Science. The N.I.H. acknowledged that the

agency does not routinely check scientists’ work for fraud as part of

the hiring process. “There is no evidence that such proactive screening

would improve, or is necessary to improve, the research environment at

N.I.H.”, said an agency spokesperson.

Charles Piller es periodista de investigación para Science. Este ensayo es una adaptación de su próximo libro, Doctored: Fraude, arrogancia y tragedia en la búsqueda de la cura del Alzheimer.