Interactions

between the immune system and the central nervous system (CNS)

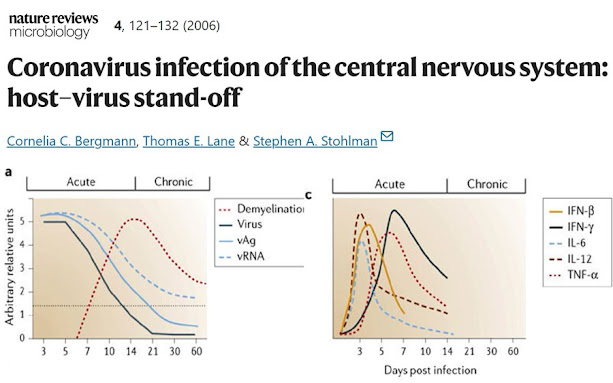

constitute the most complex and interactive regulatory network in

mammals. The high degree of specialization of cell types that comprise

the CNS, and their intricate communication, controls both cognitive and

vital functions. Disruption of the communication network and poor CNS

regenerative properties make this organ vulnerable to microbial as well

as physical injury. Although it is known that host responses must be

strictly regulated to preserve CNS function and to minimize the

incidence of autoimmunity, the factors regulating CNS immune and repair

responses are not well understood. In addition to the absence of a

dedicated lymphatic drainage system, CNS cells express few, if any,

molecules encoded by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)1,2,3.

Therefore, in the quiescent CNS there is little endogenous antigen

presentation or potential to activate T cells. Although the underlying

basis for this limited immunological activity is not completely

understood, interactions between both neurons and the glial population

represented by microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Box 1), as well as constitutive secretion of neurotrophins and transforming growth factor-β, might contribute to this quiescent resting state1,4,5,6,7. The limited expression of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and the presence of tight junctions between these cells also limit or prevent large molecules, such as antibodies, and T cells from entering the CNS2,8. Despite this, a few activated/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells randomly patrol the CNS in the absence of 'danger' signals, and either exit or die in situ in the absence of antigen recognition2,8.

Mammals have evolved many immune effector mechanisms to eliminate pathogens that infect the CNS7,9.

The vigorous inflammatory responses that are induced during many CNS

infections contrast dramatically with its quiescent steady state. These

inflammatory responses include rapidly induced, non-specific cellular

and soluble effectors that provide an innate antimicrobial defence and

facilitate development of antigen-specific effectors, which exert

antimicrobial function and establish long-lived immunological memory.

Some effectors mediate specific functions, whereas others mediate

pleiotropic effects. Furthermore, several regulatory mechanisms limit

immune responsiveness to avoid damage of uninfected host cells or the

induction of autoimmunity10,11.

The

conflicting needs for pathogen elimination and protection from cellular

damage make the mammalian CNS a partially protected environmental niche

that is a prime target for persistent viral infections. Viruses that

persist in the human CNS include DNA viruses, as exemplified by herpes

simplex virus and JC polyomavirus; RNA viruses, such as measles virus; and retroviruses, such as HIV and HTLV-1 (Refs 9,12–14).

Several viruses that establish chronic infections in the rodent CNS

provide useful models to examine both the roles and regulation of immune

effectors in this vital organ. Collectively, these models have provided

a wealth of information about the genetics of host resistance, acute

and chronic viral infection as well as host defence mechanisms. Chronic,

viral rodent CNS pathogens that are associated with myelin loss include

two well characterized RNA virus models: Theiler's murine

encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), a member of the non-enveloped Picornaviridae, and mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a member of the enveloped Coronaviridae. Although CD8+

T cells are important in controlling the acute phase of both

infections, these viruses can escape immune surveillance and establish

chronic CNS infection with ongoing myelin loss14,15,16,17,18.

Despite similar disease pathologies during chronic disease, infectious TMEV is present in the CNS during chronic disease19. By contrast, infectious MHV remains undetectable during persistence although MHV viral antigens and RNA are retained16,17,18.

Another distinguishing characteristic during chronic TMEV infection is

that chronic inflammation involves activation of self-reactive T cells20,21.

By contrast, control of infectious MHV results in a slowly resolving,

but chronic, CNS disease that is associated with minimal inflammation16,17,18.

These chronic pathological changes in the absence of overt infectious

virus are similar to human CNS diseases with suspected or potential

viral aetiologies, such as multiple sclerosis. Therefore, MHV infection

of the CNS provides a unique model in which viral replication is

controlled by a vigorous immune response but the host is unable to

achieve a sterile immunity, resulting in a persistent infection that is

associated with ongoing pathology in the apparent absence of infectious

virus.

Here, we discuss the interplay between the neurotropic

viral pathogen MHV, with emphasis on the neurotropic John Howard Mueller

(JHMV) strain, and the immune-mediated mechanisms that control acute and persistent CNS infection.

Mouse hepatitis virus

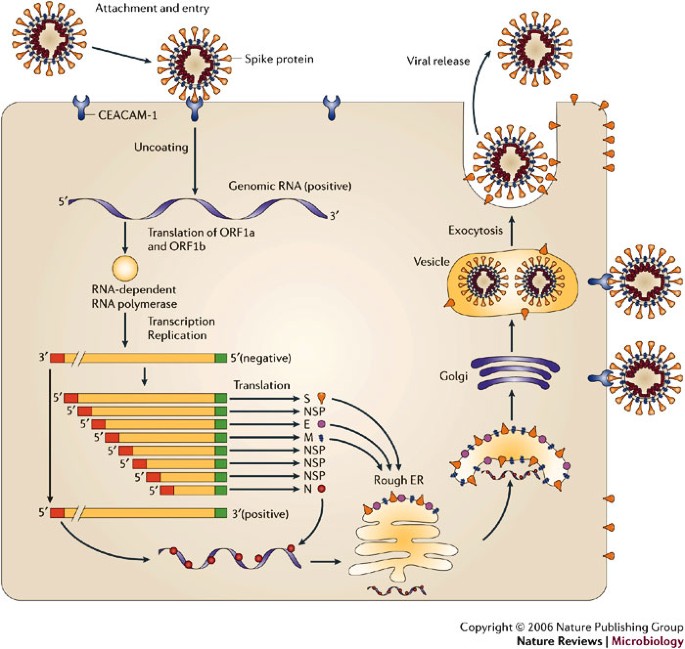

MHV is a member of the Coronaviridae family in the Order Nidovirales. The replication cycle is depicted in Fig. 1. Clinically important human coronaviruses include those that cause ∼30% of cases of the common cold and that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)22.

Bovine, porcine and avian coronaviruses also produce economically

important diseases. MHV is a natural pathogen of mice that primarily

infects the gastrointestinal tract. It produces a self-limiting

infection with residual systemic immunological defects including reduced

rejection of histo-incompatible tissues17,18.

In common with many viruses, pathogenesis and immune responses depend

on the viral strain, route of inoculation, age and genetic background of

the host. Different MHV isolates induce various acute and chronic

diseases in the murine host, including hepatitis, vasculitis, acute

fatal encephalitis and encephalomyelitis associated with acute and

chronic CNS demyelination17,18 (Box 2).

Pathogenic strategy

MHV initiates intracellular infection by

interaction of the viral-envelope spike protein (S) with its cellular

receptor, the CEACAM-1 molecule23. Analysis of S genes from MHV strains that exhibit varied pathogenesis24, selection of viruses with S-gene mutations25 and recombinant viruses with modified S genes26

all confirm that the S protein is the main determinant of cell tropism

and pathogenicity. But analysis of recombinant MHV that shows a high

degree of tropism for neurons indicates that, in the absence of the

dominant CD8+ T-cell epitope, other viral genes in addition to S genes also influence pathogenesis27,28. Adaptation to non-CEACAM-1-bearing cells can be achieved by co-culture with infected, susceptible CEACAM-1-expressing cells29, and CEACAM-1-independent infection in vitro has also been described30. These data indicate that alterations in tropism or host range might be achieved in vivo. Also, it has been suggested that receptor–S-protein affinity might contribute to the variable pathogenesis of some MHV strains31. However, not all cells that express CEACAM-1 (for instance, B cells) support MHV replication32,

indicating that other (co-)receptors and intracellular factors

influence productive virus replication. This is supported by the

efficient replication of JHMV in the CNS, despite extremely low levels

of receptor mRNA and protein expression relative to other tissues33,34. Interestingly, receptor expression on microglia decreases during CNS inflammation35, indicating that inflammatory mediators might manipulate the reservoir of susceptible cells by altering receptor expression.

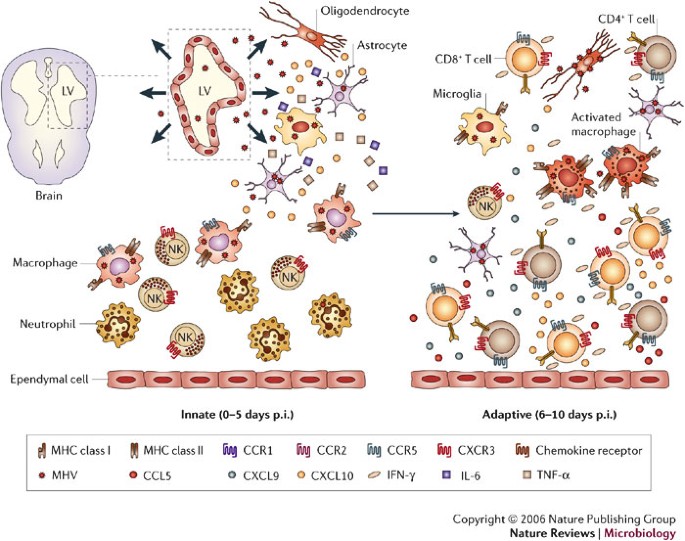

Following direct intracranial injection, JHMV infection is rapidly established in the ependymal cells that line the brain ventricles36 (Fig. 2).

As replication increases, virus spreads from the ependyma into the

brain parenchyma. The cell types that support replication include

macrophages, microglia and astrocytes, with a small number of infected

oligodendrocytes in the periventricular white matter. Virus subsequently

spreads down the central canal of the spinal cord, and moves out into

the white matter, where it predominantly infects oligodendrocytes36.

Although direct CNS injection initially disrupts BBB integrity, it is

rapidly re-established and then progressively lost as inflammation

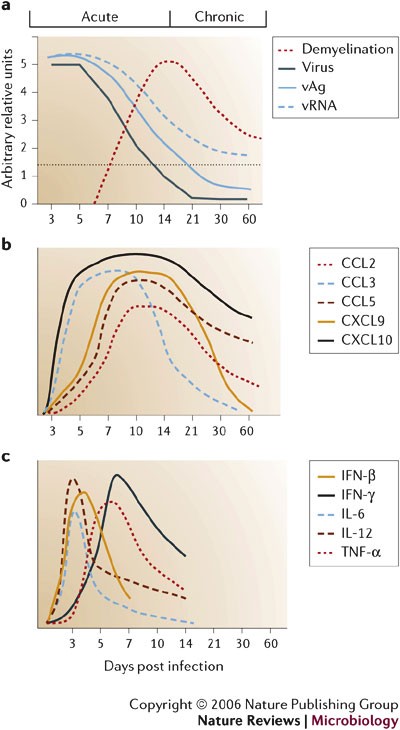

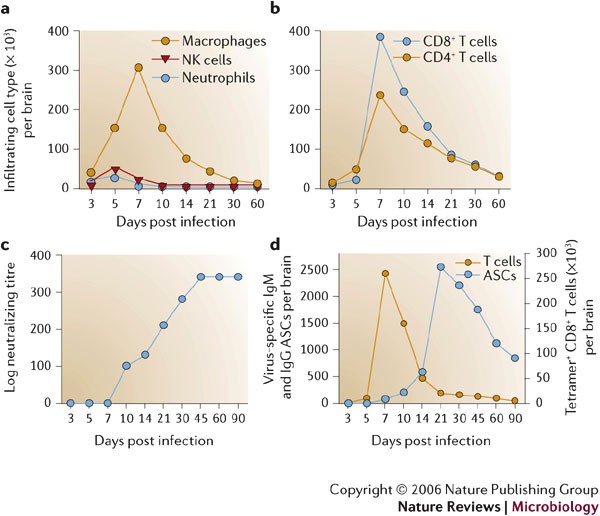

increases37. Virus replication peaks at ∼5 days post infection (p.i.) but infectious virus cannot be recovered from immunocompetent hosts by ∼2 weeks p.i.16,17,18,38,39,40 (Fig. 3a).

As viral titres increase, physiological changes such as alterations in

BBB integrity and glial-cell activation occur in the host, even in the

absence of overt clinical signs of disease. As immunity controls

infectious virus, clinical signs of disease increase25,38,39,40. Infection of immunodeficient mice indicates that clinical signs are dependent on the inflammatory response, especially the CD4+ T-cell component41,42. Prolonged detection of viral antigen and mRNA in immunocompetent mice for >1 year p.i.1,16,17,18,40,43,44,45

implies that there is incomplete immunological control of CNS virus

replication. A portion of the persisting viral RNAs are defective44,45,

which might contribute to the failure to recover infectious virus

during persistence. Virus control by inflammatory cells is associated

with primary demyelination, which is ameliorated but sustained during

the persistent state. Ongoing demyelination might be associated with

limited virus replication and concomitant immune control.

The innate immune response to acute infection

In common with other models of viral-induced encephalitis7,9,

intranasal or direct intracranial MHV infection induces a vigorous CNS

inflammatory response composed of both innate and adaptive immune

components that peaks at 6–8 days p.i.37,46. CNS infection is initially manifested by rapid, dynamic and coordinated expression of chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a tissue inhibitor of MMPs (TIMP-1) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3b,c;

0–5 days p.i.). Upregulation of these factors has largely been

characterized by mRNA analysis of whole organs to reveal overall signal

strength and patterns. However, more detailed analysis in a limited

number of studies clearly indicates that both virus-infected and

uninfected glial cells, most prominently astrocytes, provide early

inflammatory signals41,47,48.

Together, these molecules facilitate BBB disruption and attract innate

immune effectors, which express inflammatory factors. MMP expression is

associated with tissue influx of inflammatory cells, activation of

cytokine secretion and CNS damage49.

JHMV infection induces expression of MMP-3 mostly in astrocytes and

MMP-12 mostly in oligodendrocytes, independent of the inflammatory

response47,50. By contrast, a broad range of MMPs are induced in mouse models of CNS autoimmune disease49,

emphasizing the distinction between CNS infection and autoimmunity as

well as the complexity of CNS responses. Neutrophils, macrophages and

natural killer (NK) cells are the initial inflammatory cells recruited

into the MHV-infected CNS37,40 (Figs 2,4a).

Secretion of pre-packaged MMP-9 by neutrophils, upregulation of

adhesion molecules on CNS endothelium and, possibly, the action of IL-6

(Ref. 51)

contribute to a loss of BBB integrity that facilitates the subsequent

entry of further inflammatory cells into the infected CNS37. MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-12 mRNAs decrease either at the peak of JHMV-induced inflammation or rapidly thereafter47,50, supporting an early role in shaping the CNS environment. However, with the exception of MMP-9 (Ref. 37), their role(s) in innate inflammatory-cell trafficking and CNS pathology is unclear.

The earliest chemokines induced in the CNS following MHV infection are CXCL10 and CCL3 (Refs 48,52). CXCL10 is expressed by both infected and uninfected glial cells as early as day 1 p.i. (Figs 2,3b) and recruits NK cells by signalling through CXCR3 (Ref. 53).

Despite rapid but transient NK-cell recruitment into the CNS, there is

little direct evidence for an antiviral role; however, their potential

to secrete IFN-γ might facilitate antigen presentation through

upregulation of MHC class I and class II molecules. CCL3 might enhance

the adaptive immune response by stimulating T-cell activation and

recruitment52. Macrophages comprise the largest component of innate CNS infiltrates (Fig. 4a). Their accumulation is enhanced by CCL5 (Refs 41,54), which is induced with slightly delayed kinetics relative to CXCL10 and CCL3 (Ref. 48). Infection of the CNS with other neurotropic viruses, for example, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus,

TMEV and measles virus, induces chemokine-gene-expression profiles that

are similar to MHV, which indicates that CNS-resident cells respond in a

similar manner to viral infection, possibly through the expression of type I interferons (IFNs)55,56,57,58.

Cytokines

that are rapidly induced by MHV, predominantly in astrocytes and

microglia, include IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12 (Refs 59–62) (Fig. 3c).

Similar innate cytokine patterns, albeit with modified relative levels,

are also characteristic of other viral CNS infections, including TMEV, vesicular stomatitis virus, HIV and West Nile virus63,64,65.

This indicates that the secretion of these cytokines is a general,

rather than pathogen-specific or cell-type-specific, antiviral response

and is consistent with their role in the subsequent activation of adaptive immunity. TNF-α, IL-12 and IL-1β mRNA levels increase, even in the absence of inflammation59,60,62,

which indicates a resident CNS cell response to MHV infection.

Induction of the pleiotropic cytokine IL-6 might enhance

inflammatory-cell passage across the BBB, similar to its role in the CNS

autoimmune model, experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE)51.

Two

rapidly induced antiviral molecules, TNF-α and nitric oxide synthase-2

(iNOS, the inducible NOS isoform), which influence immunity to other CNS

viral infections62,63,64,65,

seem to have no role in the anti-MHV host response. Although iNOS mRNA

levels increase in the CNS of MHV-infected immunocompromised mice and

although iNOS suppresses virus replication in vitro66, no role for iNOS in controlling CNS virus replication was detected in vivo67,68. The reduced mortality of MHV-infected iNOS-deficient mice might be due to its contribution to neuronal apoptosis69. Despite increased TNF-α transcription during MHV infection in vitro and in vivo, translation is inhibited in MHV-infected cells70.

However, TNF-α is produced by uninfected microglia within the inflamed

CNS, indicating that translation might only be impaired in the minor

fraction of MHV-infected microglia in vivo70. In contrast to its role as an antiviral effector and mediator of myelin loss during EAE71, neither MHV replication in vivo nor CNS pathology are altered in the absence of TNF-α70,72.

The adaptive immune response

Virus replication and spread increases despite the innate response, although innate immunity

facilitates the induction, recruitment and effector function of

adaptive immune components. Accumulation of virus-specific T cells,

especially the CD8+ T-cell component, correlates with a

marked decrease in virus replication in astrocytes, microglia,

macrophages and oligodendrocytes. Distinct antiviral mechanisms control

virus replication in a CNS-cell-type-specific manner. As virus

replication is controlled, the number of inflammatory cells decreases;

however, viral persistence is associated with the CNS retention of

immune effectors.

Activation of naive T cells. Initial virus replication in the ependymal cells that line the cerebral ventricles36 (Fig. 2)

probably facilitates the activation of adaptive immune responses by

drainage of antigen into the cervical lymph nodes (CLN) through the cerebrospinal fluid, which connects the CNS to the lymphatic system7,8.

This pathway is consistent with a model in which initial virus-specific

T-cell activation occurs in the CLN, followed by chemokine-directed

T-cell trafficking into the CNS. By contrast, stereotactic instillation

of antigens, viruses or viral vectors directly into the CNS under

conditions that maintain BBB integrity elicits poor adaptive immune

responses, presumably owing to the relative isolation of the CNS and

immune systems73,74.

No detectable JHMV replication occurs at peripheral sites; however,

virus-specific T cells are detected in the CLN prior to detection in the

CNS or spleen75.

Although adaptive immunity seems to be initiated in the CLN, whether

infectious virus or only viral antigens are present in CLN and the

identity and origin of MHV-specific antigen-presenting cells are

unclear. Bone-marrow-derived circulating monocytes that are recruited

into the CNS as an innate immune component might differentiate into

macrophages or dendritic cells and present antigen in the CNS21,76.

Alternatively, antigen-presenting cells might acquire viral antigens

within the CNS and subsequently enter the CLN. The latter possibility is

supported by detection of cells with a dendritic-cell-like phenotype in

the CNS parenchyma and CLN as early as two days p.i.77.

Therefore, it is plausible that, following phagocytosis of viral

antigens and exit from the CNS, dendritic cells or macrophages in CLN

provide an initial source of antigen presentation that is required for

activation and expansion of virus-specific T cells.

Alterations in chemokine and cytokine patterns.

Chemokine expression by infected and uninfected CNS cells and changes

in receptor expression by peripherally activated adaptive immune

components alter the dynamics of CNS-infiltrating cell populations.

Chemokines that are expressed during the adaptive immune response to

acute MHV infection include CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5, and

there is corresponding expression of the chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR5

and CXCR3 (Fig. 3b) (Ref. 48).

This chemokine pattern in the infected CNS is not specific for MHV

infection; microglia and astrocytes synthesize chemokines following

infection with both RNA and DNA viruses in the absence of inflammatory

cells63,64.

Similar to the innate immune response, CXCL10 is the prominent

chemokine expressed during the adaptive phase of acute infection,

consistent with an important role in promoting neuroinflammation. CXCL9

and CXCL10 attract activated NK and T cells that express CXCR3 (Refs 53,78,79). Supporting their central role in effector recruitment, inhibition of CXCL9 and CXCL10 increases MHV-induced mortality78,79.

Increasing

accumulation of T cells as BBB integrity becomes compromised at 6–8

days p.i. coincides with a decline in neutrophils and NK cells (Fig. 4), although it is not clear if these cells exit the CNS or die in situ.

By contrast, macrophages persist in the CNS; however, their phenotype

alters owing to increased MHC class II expression that is driven by

increasing concentrations of T-cell-derived IFN-γ. Although most early

T-cell infiltrates are memory T cells specific for irrelevant antigens,

these are replaced by virus-specific T cells, which expand in secondary

lymphoid organs and migrate into the CNS parenchyma80. As antiviral T cells accumulate in the CNS, there is a concomitant decline in infectious virus (Fig. 3a).

The reduction in CNS viral burden is reflected in the modulation of

immunological markers associated with maximal viral replication. For

example, chemokine transcripts that encode CXCL9, CCL2, CCL3 and CCL7

are notably reduced48. Similarly, proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IFN-β) decline60. By contrast, the T-cell chemoattractant chemokines CXCL10 and CCL5 remain elevated48, correlating with increased T-cell recruitment and IFN-γ expression40,60 (Fig. 3b,c). Unexpectedly, TNF-α mRNA levels decrease before those of IFN-γ60,

although virus-specific T cells can secrete TNF-α. Among its many

biological activities, IFN-γ has direct antiviral activity and induces

MHC expression on CNS-resident cells, facilitating interactions between

immune effectors and CNS-resident cells. In the absence of IFN-γ, MHC

class I expression is reduced and MHC class II remains undetectable on

microglia46,81 and most macrophages81

during JHMV infection. Indeed, peak IFN-γ mRNA levels coincide with

peak T-cell infiltration, and IFN-γ protein is functionally evident in

the inflamed CNS by maximal expression of both MHC class I and II on

microglia46,60,81.

T-cell infiltration and antiviral effector functions.

Novel concepts emerging from MHV-induced CNS infection are the

differential abilities of T-cell subsets to migrate within the CNS and

the crosstalk between T-cell subsets. CD4+ T cells cross the

BBB, but instead of trafficking to parenchymal sites of virus

replication, they accumulate around blood vessels82. By contrast, CD8+ T cells enter the parenchyma after migrating through the BBB. The differential ability of CD4+ T cells versus CD8+ T cells to traffic through the infected tissue is associated with expression of TIMP-1 by CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells47.

These data indicate that, rather than expression of a protease to

promote migration, expression of a protease inhibitor prevents migration

of CD4+ T cells into the CNS parenchyma. In the absence of CD4+ T cells, parenchymal CD8+ T-cell infiltration is dramatically decreased and is associated with increased apoptosis82, indicating that CD4+ T cells, either directly or indirectly, provide factors that are required for both the migration and the survival of CD8+ T cells within the CNS. Although IL-2 has been excluded, other survival factors remain unidentified83.

During peak T-cell accumulation, most CD8+ and CD4+ T cells within the CNS are virus specific16,40. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate to 10-fold higher frequencies in the CNS compared with the periphery and they express the CD44hi, CD62L−/lo, CD11ahi and CD49d (VLA-4) activation/memory phenotypic markers40, which is consistent with their crucial role in controlling acute MHV replication40,75. CD43hi and CD127−/lo expression discriminates virus-specific CD8+ T cells within the CNS from those T cells specific for irrelevant antigens, which retain a CD43int, CD127+ phenotype80.

Although the early activation marker CD69 is only transiently

upregulated early during priming and expansion of T cells in secondary

lymphoid organs, CD8+ T cells recruited into the CNS during JHMV infection retain CD69 expression40, consistent with other CNS-inflammation models84.

Virus-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from the acutely inflamed CNS secrete IFN-γ, express granzyme B and are efficient cytolytic effectors40,85. These T cells accumulate within the CNS coincident with inhibition of infectious virus, and transferred memory CD8+ T cells control virus replication in immunodeficient hosts40,46, confirming their role as primary effectors of virus clearance. Compared with highly activated CD8+

T cells obtained during acute infection, virus-specific memory T cells

are superior at controlling virus replication in immunodeficient hosts42,72. This enigma might reflect an increased sensitivity of highly activated CD8+ T cells to activation-induced apoptosis, or their preferential accumulation in peripheral compartments86.

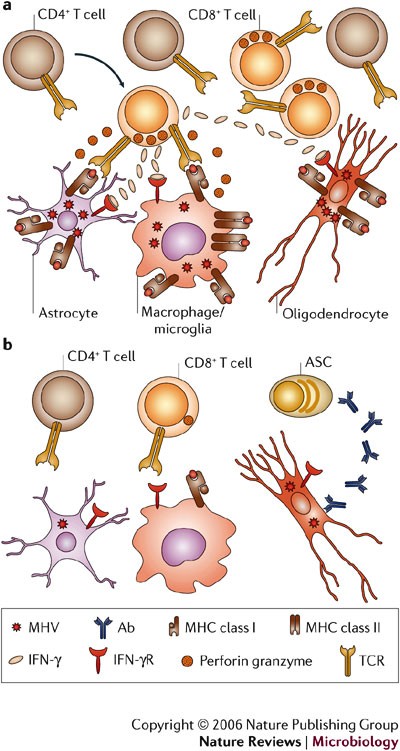

T-cell antiviral effector mechanisms are cell-type specific. In mice deficient in perforin-mediated cytolysis, viral replication is uncontrolled in macrophages, microglia and astrocytes38. However, infection of oligodendrocytes is controlled in the absence of cytolysis38. These results indicate that an effector mechanism distinct from MHC class I recognition by CD8+ T cells controls virus replication in oligodendrocytes. By contrast, the absence of the Fas/FasL cytolytic pathway does not alter pathogenesis, virus clearance or pathology87.

In IFN-γ-deficient mice that are competent for perforin-mediated

cytolysis, virus replication is controlled in astrocytes and microglia,

but not oligodendrocytes39. The distinct use of effector mechanisms in the control of viral replication by CD8+ T cells was confirmed by adoptive transfer of CD8+ T cells deficient in either cytolytic activity or IFN-γ secretion into infected immunodeficient hosts40,46.

Furthermore, infection of mice with a selective defect in IFN-γ

signalling in oligodendrocytes confirms that direct IFN-γ signalling is

required to control oligodendrocyte infection88. These data support the concept that the mechanisms of CD8+ T-cell-dependent control of virus replication are cell-type dependent.

Pathway to persistent infection

After infectious MHV is eliminated at ∼2 weeks p.i., inflammatory cells, viral antigen and viral mRNA persist in the CNS (Fig. 3a). Virus-specific CD8+ T-cell cytolytic activity is rapidly lost by day 14 p.i., as viral-antigen concentrations decrease40,85. Whether the loss of cytolytic function is due to decreased antigen89 or reflects an attempt to limit the potential adverse effects of cytolysis on CNS cells is not clear.

The contribution of CD8+

T-cell escape variants to persistent infection depends on mouse strain,

age and immune status. Little evidence for escape mutants has been

detected during virus persistence in naive mice infected as adults45 or in mice undergoing reactivation owing to the absence of humoral immunity38.

Nevertheless, progressive accumulation of viral quasispecies with

deletions in the S-protein hypervariable domain, which contains the

immunodominant H-2b CD8+ T-cell epitope, was found in persistently infected H-2b

mice. Secondary-structure analysis indicated that the deleted regions

reside in an RNA stem-loop structure that forms a 'hot spot' for RNA

recombination90,

questioning the extent to which the S mutants emerged from immune

pressure. Mutations in this S-protein epitope were clearly associated

with increased infectious virus in the CNS following infection of

neonatal mice protected by maternal antibody91. A potential for immune escape was also shown when pre-immune mice that harboured CD8+ T cells specific for a novel epitope were challenged with the recombinant MHV-A59 strain that expressed the same epitope27.

Taken together, these data indicate that T-cell escape variants do not

have a prominent role in the persistence of virus after infection of

naive adult mice, but might readily emerge in genome regions that do not

affect viral fitness, especially under conditions of pre-existing

antibody or T-cell memory.

CD8+ T cells that are found

in persistent CNS MHV infection are not impaired in IFN-γ secretion,

which indicates that loss of cytolytic function is not due to the

induction of an anergic state. However, impaired virus-induced TNF-α secretion by CD8+ T cells during both acute infection and persistence85

indicates that T-cell retention within the CNS might be due to

decreased secretion of apoptosis-inducing factors. The loss of CD8+

T-cell-mediated cytolysis during resolution of primary MHV infection

and throughout persistence contrasts with the retention of cytolytic

effector function in reactivated T-memory cells following neurotropic

influenza-virus challenge84. However, increased granzyme B levels in reactivated MHV-specific memory CD8+ T cells, compared with primary CD8+ T cells isolated from the CNS following challenge, supported the retention of intrinsic cytolytic function85.

These data show that the loss of virus-specific cytolytic function is

not an intrinsic property of the inflamed CNS environment, but reflects

distinct differentiation states of primary CD8+ T cells compared with vaccine-induced memory CD8+ T cells.

Virus-specific

T cells decline markedly between 10 and 21 days p.i., but are retained

for at least 3 months following clearance of infectious virus43,85.

The initial T-cell decline in the CNS is similar to, but not as

prominent as, the decline of T-cell effector populations in peripheral

lymphoid organs following antigen elimination and withdrawal of cytokine

survival factors92,93. Nevertheless, CNS retention of small numbers of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells40,43

indicates that the myelin-loss characteristic of the persistent phase

of MHV infection is associated with a continuing immune response,

sustained by low-level oligodendrocyte infection. Sustained CD69

expression also distinguishes CD8+ T cells that are retained

within the CNS from resting peripheral memory cells in lymphoid organs,

and suggests chronic activation40 or an effector memory phenotype characteristic of memory T cells residing in non-lymphoid tissues92. Antigen-driven T-cell persistence was indicated by the limited T-cell-receptor specificities found in CD8+ T-cell populations isolated during MHV persistence compared with T cells isolated during acute infection94. Complete disappearance of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from the CNS following infection with a neurotropic MHV43 not associated with viral persistence or myelin loss25 supports a role for viral persistence or continuing pathology in maintaining T-cell retention.

The

contribution of local proliferation or ongoing recruitment to the

T-cell population that persists in the CNS remains unclear. Indeed,

IL-15, which regulates antigen-independent homeostasis of memory cells

in lymphoid organs93, is not required for CD8+ T-cell retention in the CNS (C.C.B., unpublished data). Adoptive transfer of CD8+

T cells into persistently infected mice further indicates that there is

limited recruitment to the CNS compared with the acute phase (C.C.B.,

unpublished data). These data are consistent with the recent

observations that memory T cells traffic poorly into the CNS92

and that activated T cells recruited in response to acute infection are

only retained within the CNS on cognate antigen recognition2,7,8. Overall, analysis of persistent MHV infection indicates that CD8+ T-cell turnover within the CNS is limited and does not comprise significant ongoing peripheral recruitment.

Humoral effectors and control of CNS persistence

Serum antibody that is present prior to MHV

infection, either due to systemic administration or immunization,

provides protection, although not necessarily by inhibition of virus

replication. Virus-neutralizing antibody and antibodies with no apparent

neutralizing activity modify MHV-induced CNS disease if passively

transferred prior to infection17,18. Transport of neutralizing antibody into the CNS parenchyma owing to the loss of BBB integrity50

might limit the replication of challenge virus by inhibiting receptor

binding. A complement-dependent role in protection for antibodies

lacking neutralizing activity is less clear95 although at least one nucleocapsid-protein-derived epitope is expressed on the MHV-infected cell surface96, providing a potential recognition structure.

Antibody responses in infected naive animals are delayed relative to the vigorous cell-mediated immune response (Fig. 4c,d).

Serum antibody, including neutralizing antibody, is virtually

undetectable and predominantly limited to IgM prior to the complete

elimination of infectious virus (Fig. 4c,d).

Furthermore, mice that lack humoral immunity control CNS-infectious

virus with kinetics similar to immunocompetent mice, accompanied by a

normal inflammatory response during acute infection97,98. These data are consistent with the concept that control of acute infection is independent of humoral immunity17,18.

However, in contrast to wild-type mice that recover, mice that are

unable to secrete antibody show increased mortality after resolution of

acute disease, associated with the re-emergence of infectious virus

within the CNS97,98.

Interestingly, the A59 strain of MHV, which infects both the liver and

CNS, fails to reactivate in the liver in the absence of humoral immunity99.

Whether this is due to the absence of viral persistence in liver or

reflects a fundamental difference in immune control in these two organs

is not clear. Passive transfer of neutralizing, but not nonneutralizing,

viral-specific antibody into B-cell-deficient mice following initial

virus clearance prevents virus reactivation, confirming the crucial role

of antibody in regulating CNS viral persistence100.

The inability of transferred non-neutralizing antibody to prevent virus

recrudescence is inconsistent with the apparent protective role for

non-neutralizing antibody prior to infection. Interestingly, infectious

virus reactivates as passive antibody levels decline, supporting a

requirement for CNS retention of antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) in

providing long-term control of persistence.

MHV-specific ASCs accumulate rapidly after control of infectious virus during persistence101 (Figs 4c,5).

Although ASCs that are not specific for MHV are present in the CNS

during the virus-clearance phase, only a few virus-specific ASCs are

detectable in either the CNS or peripheral lymphoid system during acute

infection101, consistent with the inability to detect serum antibody. Both populations are retained after virus is cleared101. The preceding peak of virus-specific IgG ASCs in CLN ∼1

week prior to peak CNS accumulation indicates initial ASC activation

and differentiation in CLN and spleen prior to CNS migration.

Virus-specific ASCs are retained in the CNS at high frequencies for at

least 3 months p.i., indicating that ASC-specific survival factors are

present in the CNS during viral persistence. Despite their progressive

decline, virus-specific ASCs are maintained at higher levels than

virus-specific T cells40,101. The CNS has been shown to be a survival niche for ASCs following Sindbis-virus- and Semliki-Forest-virus-induced encephalitis102,103.

The accumulation and maintenance of virus-specific ASCs in the CNS,

coupled with reactivation of infectious virus in the absence of

antibody, indicates that antibody secretion within the CNS, and not

T-cell immunity, is crucial for the control of MHV CNS persistence.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Analysis of the MHV model highlights the diversity

of immune responses that is required to prevent subsequent pathology

associated with a persistent infection confined to a single target

organ. This model supports a paradigm in which cell-mediated immunity

affects clearance of infectious virus through mechanisms that are

dictated by the specific cell type within the infected tissue (Fig. 5).

Although effective in controlling acute virus replication, T cells are

ultimately unable to achieve sterile immunity or suppress virus

reactivation, most likely owing to downregulation or inhibition of

destructive effector functions in vivo. However, cessation of

T-cell function is complemented by a wave of virus-specific ASCs that

are recruited into the CNS following resolution of acute infection. In

contrast to T cells, ASCs are maintained within the CNS at high

frequencies during virus persistence. These data indicate that local

secretion of neutralizing antibody within the CNS maintains virus at low

levels, thereby providing a protective in situ effector system preventing virus recrudescence (Fig. 5).

Many

issues related to neurotropic MHV infections remain unresolved.

Contributions of alternative receptors, co-receptors or

receptor-independent spread to tropism and pathogenesis are still

elusive. Viral components involved in cell signalling through viral

receptors, Toll-like receptors or type I IFN pathways are also largely

unexplored. Distinct MHV isolates, combined with powerful new genetic

tools26,27,28,

promise to shed light on these pathways. Differential cell

susceptibility to antiviral mechanisms also requires further

investigation38,39,46. Specifically, the ability of mature glial cells to present viral antigens104,

regulation of ligands affecting lymphocyte function, and factors

involved in apoptosis are of interest. Similarly, the responsiveness of

resident CNS cells to IFNs in vivo is largely unknown88. The role of dendritic cells during virus-induced CNS inflammation, as well as CD4+ T-cell contributions to CD8+ T-cell function within the CNS82,

also requires evaluation. Last, an intriguing question is how, and in

what form, virus persists, although a replication-competent form is

implicated by virus recrudescence in the absence of humoral immunity97,98.

Resolving mechanisms of viral persistence might also elucidate events

associated with ongoing immune activation and T-cell and ASC retention,

all potentially contributing to demyelinating disease.

Acute, potentially lethal viral infections of the human CNS, for example, West Nile virus and Saint Louis encephalitis virus, primarily target neurons105.

Other human viruses, for example, herpes viruses, target and remain

latent in neurons. HIV and JC polyomavirus primarily target other CNS

cell types and are prone to producing latent or persistent CNS

infections9,12,13.

Although it is unclear how SARS-virus CNS replication contributes to

pathogenesis, recent data also confirm CNS virus infection106.

Coronavirus

infection of the CNS has provided unique insights into the immune

regulation of acute and persistent infection at the cellular level of a

natural rodent pathogen, and provides a model for studying chronic

demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis. Delineation of the

dynamic interactions that regulate acute and persistent infections of

the CNS has implications for vaccine design as well as for the

development of novel immunotherapeutics to limit viral replication and

attenuate the potential damaging effects of the immune response within

the CNS.

Box 1 | CNS cell types

The

central nervous system (CNS) is composed of two main cell types:

neurons and glial cells. The three main types of glial cells are

astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia.

Glial cells

Microglia. Microglia are the

myelomonocytic lineage-derived resident 'macrophage' population of the

CNS. They have many characteristics common to other tissue macrophages.

However, microglia express only low levels of CD45,

a marker of bone-marrow-derived cells, and unlike tissue macrophages,

they also proliferate. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules

are not expressed on microglia in the undisturbed CNS, but are rapidly

expressed following exposure to IFN-γ. In addition to mouse hepatitis

virus (MHV), murine microglia are the targets for Theiler's murine

encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection, and human microglia are the

targets of HIV and JC polyomavirus infection.

Astrocytes.

Astrocytes are the most abundant CNS cell population. Astrocytes

interact with CNS endothelial cells to form the blood–brain barrier. In vitro data suggests a potential role for astrocytes in antigen presentation; however, little in vivo data is currently available. Expression of MHC molecules in situ

is also controversial. Astrocytes support the replication of the John

Howard Mueller (JHMV) strain of MHV in the murine CNS and of HIV and

adenoviruses in the human CNS.

Oligodendrocytes.

Oligodendrocytes produce a lipid- and protein-rich laminated myelin

membrane that surrounds axons and promotes axonal conduction. In

addition to supporting JHMV replication in the murine CNS,

oligodendrocytes support JC-polyomavirus and measles-virus infection in

the human CNS.

Neurons

Neurons are the main cell type involved in motor

and cognitive function. The JHMV variants differ in their ability to

infect neurons. Neurons are primary targets in the murine CNS for many

diverse viruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus, Sindbis virus, West Nile virus, vesicular stomatitis virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Human neurons are targets of herpesvirus, poliovirus and rabies virus in the human CNS.